|

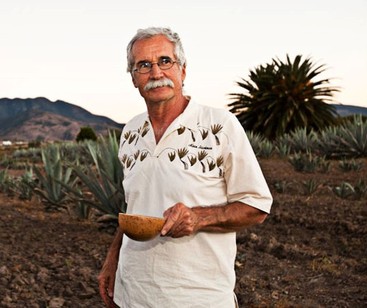

Alvin Starkman began drinking mezcal in 1969 during his first visit to Oaxaca, and then continued the love affair the following summer. However it wasn’t until 1991 that he started to become an aficionado, interested in learning, sampling, expounding the spirit’s attributes to others, and promoting its producer palenqueros.

Alvin has an M.A. (Social Anthropology, York University) and a J.D. (Osgoode Hall Law School). Throughout his academic training he maintained a special interest in cross-cultural dispute resolution, with emphasis on Mexican models. He spent 18 years as a litigation lawyer in private practice in Toronto, before becoming a permanent resident of Oaxaca in 2004. Alvin first became passionate about pulque when he began living in the city full-time. He eventually started taking tourists to Oaxaca into the fields accompanied by his Zapotec friends, to enable them to experience the fascinating harvest of aguamiel – the “honey water” which transforms into pulque as it naturally ferments. Alvin has written over 260 articles about life and cultural traditions in Oaxaca, several of which center upon mezcal and pulque. He is a paid contributing writer for Mexico Today, a program for Marca País – Imagen de México. Alvin continues his pursuit of exposing all that is culturally rich about Oaxaca and its central valleys, by helping travelers to the city to plan their visits, including touring the central valley routes – with a special interest in helping them to learn as much as possible about mezcal and pulque. Together with his wife Arlene, Alvin operates Casa Machaya Oaxaca Bed & Breakfast (http://www.oaxacadream.com), and with Chef Pilar Cabrera Arroyo, Oaxaca Culinary Tours (http://www.oaxacaculinarytours.com). He is a director and Vice-President of CANFRO (Canadian Friends of Oaxaca Inc.), a Canadian charitable corporation. Alvin’s predominate thirst remains promoting mezcal and pulque to tourists and spirits aficionados, including assisting those interested in pursuing the export of agave based alcoholic beverages from Mexico to their home countries and indeed further abroad.

1 Comment

In a quirky turn of fate, just as craft beer consumption in Oaxaca has begun to skyrocket, South Africans who have traditionally preferred microbrewery beers to commercial brews and spirits, are now turning their attention to mezcal. In January, 2012, Oaxacan-distilled La Muerte brand mezcal hit the shelves in South Africa.

Until recently, mezcal (also referred to as mescal), the spirit derived from a number of varieties of agave (or maguey) plant, took a back seat to its more popular sister, tequila. But with the aid of a marketing plan currently being advanced by the Mexican government through its ProMéxico agency, the southern state of Oaxaca, producer of most of the country’s mezcal, has become the darling of up and coming spirits importers. Enter entrepreneur Rui Esteves. In less than two months his La Muerte mezcal has become the top selling Mexican spirit at popular Cape Town restaurant El Burro, known for its broad selection of tequilas; no small feat given that La Muerte had to dislodge popular products such as Patrón and Olmeca from their lofty rankings. Since 2007, Esteves’ main business interest has been beer, importing German craft beer to South Africa, and promoting it through an innovative and aggressive marketing plan. Then about three years ago Esteves began introducing tequila and other agave based spirits (as well as agave nectar) into the South African marketplace. The agave business began strictly as a hobby, with Esteves tapping the advertising acumen he’d honed during his dealing with imported brews. But for Esteves it’s always been much more than his expertise in marketing and promotion which has driven his products, and in this case La Muerte mezcal. “I love working with artisan producers who are driven because of the pride they have in what they brew or distill,” he notes. “And just as importantly,” he continues, “I only work with products that I love to drink myself and that form part of my life; I have no passion for whiskey, and hence I don’t work with it.” And so Esteves travelled to Oaxaca about 1 ½ years ago with mezcal in mind. He met with a number of palenqueros (producers), sampled their products, and subsequently decided to work with one individual in Matatlán, a town about a 45 minute drive out of Oaxaca and reputed to be “The World Capital of Mezcal.” It must be; a sign stretching across the highway as you enter Matatlán tells you so; and above the sign there’s a full-size copper still. “It was important for me to sit down with the palenquero and his wife and family in their home before making a decision about working with them,” he explains. “Meeting the rest of the family affirmed for me their passion for what they do, and learning that they have a mezcal producing tradition in Matatlán which dates to the 1800s didn’t hurt either.” Although mezcal had previously been available in South Africa, imbibers really didn’t have any idea about what it was or how it was made until La Muerte came on the scene. And of course the products which were available were not of the artisanal quality that Esteves has now introduced. Tequila struggled with its reputation until the Patróns began to be imported. It’s taken until now for the drinking public to gain an appreciation for mezcal, through La Muerte. “South Africans are embracing it; they can’t believe it actually tastes delicious,” he proudly asserts. Esteves initially chose reposado con gusano because he felt that it was a spirit which could be easily marketed at an accessible price. His other entry into the mezcal market, a five-year añejo aged in Kentucky bourbon barrels, came about as a result of a spontaneous emotional decision. “I just fell in love with it,” he confesses, then adds, “what I feel about quality mezcal, and in fact about the magic of Oaxaca, I want to share with my countrymen and women.” And the branding? Esteves could have selected any one of a number of names. “Oaxaca is filled with inspiration,” he gleams. “The name was influenced by Day of the Dead of course; and the respect Oaxacans have for the dead, and more generally their ancestry and heritage.” Despite the meteoric rise in popularity of La Muerte mezcal over the past couple of months, Esteves maintains that to date he really hasn’t done much marketing and that for the time being he’s just planting the seed and gauging mezcal’s potential, in South Africa and as well in other non-traditional markets for agave based Mexican spirits. Esteves is cognizant of the recent trendiness in some large American cities, and indeed in some parts of Mexico, of mezcals made from not only agave espadín which is used to make his reposado and añejo, but some wild and other “designer” magueyes. But he remains cautiously optimistic, planning to introduce other mezcals into select markets by taking slow, deliberate steps. “I tend to get carried away,” he confesses. But judging from the initial welcome of La Muerte mezcal in South Africa, the more hastily Esteves proceeds with his plan, the better for Oaxacan palenqueros, for Mexico’s economic fortunes, and for South Africans. And if Esteves keeps to his course, brewers of craft beers beware. Mezcal, whether produced in Oaxaca or in other Mexican states, struggles to get the recognition it deserves, and more importantly the foreign revenue it’s capable of generating for Mexico. Hence ProMéxico has taken the bull by the horns and is attempting to elevate the image of mezcal to par with not only tequila, but also scotch, vodka, gin, brandy and all the other household spirit names.

“We’re trying to position mezcal on the international stage, by creating an accurate image,” says Thalia Friligos Reyes, the sole representative of ProMéxico in the state of Oaxaca. “That’s how we’ll succeed. First we must create a positive perception. Without it, the umpteen brands of mezcal produced in Oaxaca mean little.” In her view, tequila doesn’t need the same level of assistance from the Mexican government. “Tequila is already up there with the other major spirit classes; mezcal isn’t,” she says. “Too many people still have the erroneous idea that all mezcal is strong, cheap and has the worm. But in the two years I’ve been at the helm of the ProMéxico Oaxaca office, I’ve noticed a positive change, albeit somewhat minimal, in consumer attitude and knowledge.” In a recent interview, Ms. Friligos nevertheless acknowledged that her task is daunting. And to top it off, from her small office in suburban Oaxaca she’s in charge of promoting international investment in and export of all goods and services in Oaxaca, not just mezcal. ProMéxico is one of the newest agencies of the government of Mexico, formed in 2007. Its stated mission is to “plan, coordinate and execute strategies to attract foreign direct investment, promote Mexican exports of goods and services and encourage the internationalization of Mexican companies in order to contribute to the economic and social development of Mexico.” Ms. Friligos’ office contains shelves packed with product samples and promotional materials. They serve as a reminder that she’s in charge of everything produced in Oaxaca. But it’s the consumables which stand out; chocolate, coffee, sal de chapulín, instant tejate mix, and of course mezcal. She stresses that coffee, mangos and mezcal are three key products for her. “But the first two don’t need the same help as mezcal,” she continues, “either in terms of recognition as quality Mexican foodstuffs, or in order to obtain a fair market share. Look at the number of mezcal producers in the state compared to the relatively few export producers of mangos, and even less when it comes to coffee. Coffee and mangos generate healthy revenue from few producers. Then consider mezcal in Oaxaca; there are so many producers in such a large, untapped global marketplace.” ProMéxico Event Promotes Oaxacan Mezcal Internationally In July, 2011, for the third year running, Ms. Friligos, with the support of ProMéxico’s head office and assistance from her counterpart in Puebla, brought international spirits vendors and promoters to Oaxaca for a three day promotional mezcal event. ProMéxico has 28 regional headquarters in 21 foreign countries. The network of offices keeps an accurate pulse of developments in the world of spirits. In this way each year ProMéxico is in a position to know who on balance would make good investments of time and money in terms of extending invitations to its events and hosting its guests. The 2011 conference was attended by 10 invited guests from Canada, the US, Brazil and Colombia. Some brought along spouses or business associates, bringing the total number of participants to about 20. It was no coincidence that the mission took place during Oaxaca’s annual Feria Nacional del Mezcal, a multi-faceted event with a singular main draw for tourists and residents alike: an opportunity to sample a broad variety of mezcals from the dozens of small booths set up by participating mezcal producers. “ProMéxico operates its event independent of the mezcal fair,” Ms. Friligos clarifies. “The Feria Nacional del Mezcal is essentially a state supported and organized event, held in cooperation with COMERCAM (Consejo Mexicano Regulador de la Calidad del Mezcal A.C. – the regulatory body which oversees commercial production of mezcal for predominantly international export). “But inviting a group to come down while the fair is on makes it that much more diverse an experience for our guests,” Ms. Friligos continues. “The Feria del Mezcal helps to give them a more complete picture of what Oaxaca is all about; craft and food booths, overall ambiance, of course getting a sense of the widespread interest in mezcal, and that feeling of exhilaration that is a byproduct of attending any festive event in Oaxaca. Mezcal is almost synonymous with Oaxaca, so it’s important for our clients to experience as much as possible of what Oaxaca has to offer.” Guests arrived throughout the day on July 27th, and were taxied to Hotel Misión de Los Ángeles, one of the larger Oaxacan hotels, selected both because of its conference facilities and convenient location within walking distance of the grounds of the Feria Nacional del Mezcal. The first evening dinner, as one might have guessed, included mezcal tastings at a nearby restaurant. It also played host to a Guelaguetza, the famed folkloric festival showcasing the dress, dance and music of Oaxaca’s 16 indigenous cultures. The next two days were spent in plenary sessions, meeting 20 different mezcal producers to learn about their spirit lines, production methods and of course export capabilities. Later on during the afternoon of the 28th guests attended the mezcal fair, and the following day a lunch at acclaimed Oaxacan restaurant Los Danzantes. Federal government representatives and state dignitaries were in attendance, including Oaxaca’s secretary of tourism and economic development. As with many successful events, and this conference was no different, there’s often not enough time to fit in every agenda item. The group was unable to visit one of the out-of-town mezcal factories (fábricas de mezcal). However, a couple of guests did manage to snag a factory rep and have him drive them out to his fábrica in the Tlacolula mezcal producing region. The evenings were allocated as free time, to give the prospective buyers and promoters an opportunity to return to the mezcal fair, explore downtown Oaxaca on their own or in small groups, and meet for more serious discussions with their choice of individual producers. ProMéxico´s Oaxaca Mezcal Mission Achieves Its Goals “We couldn’t have asked for a more successful event,” Ms. Friligos beams. “Everyone was thoroughly impressed with Oaxaca, but more importantly from the perspective of ProMéxico and its goals, our guests left with a new understanding about mezcal. To the extent that anyone in the group had lingering misperceptions about mezcal, they were dispelled through our ability to fully educate. “Through the seminars, discussions and samplings, our guests left appreciating that mezcal can be used as a mixer just as easily as for sipping, given the diversity of product,” she continues. Then returning to the concern that mezcal may be slow to catch up to tequila, Ms. Friligos points to the significant advantage that mezcal has over its sister spirit. “Although there are tremendous variations in tequilas based on producer, recipe, and aging, tequila production is restricted to using one variety of agave. Mezcals, on the other hand, are made from 15 – 20 different types of agave, as well as blends, resulting in a much broader variation in flavor and other subtle nuances simply not achievable with tequila.” Just two shorts weeks after the conclusion of the 2011 ProMéxico Oaxaca mezcal event, three of the 10 invited guests had already taken first steps towards importing Oaxacan mezcal with the assistance of ProMéxico and Ms. Friligos. A Brazilian is importing four brands of mezcal; a Dallas beer importer is also bringing in four brands, initially to supplement his brewed product lines; and a New York businessman representing importing and retailing interests is proceeding with a long term plan to import eight to ten brands. If ProMéxico meets with equal or greater success from its next two or three Oaxacan mezcal missions, by 2015 mezcal should indeed be on par with scotch, vodka, gin and brandy, and yes tequila. Mezcal has always been associated with the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca, since the region in and around its central valleys has traditional been known as the largest and most important producer of the spirit. Santiago Matatlán, a town about 45 minutes outside of the city of Oaxaca, boasts being the world capital of mezcal. It’s home to about 150 palenqueros (mezcal producers). A full size copper still stretches majestically across the highway at its entranceway. So what better city than Oaxaca to host the Feria Nacional del Mezcal, an annual festival dedicated to exalting and promoting the agave based alcoholic beverage “with the worm.”

Over the past several years the worm has actually adversely impacted the perception of mezcal as a spirit worthy of sipping and mixing. The other main impediment has been mezcal’s lingering reputation with the college crowd as the Mexican spirit used to get inebriated, fast and furiously. Hence tequila’s little sister has always had a rough time of it both in Mexico and further abroad. But with the arrival of the new millenium things began to change for Plain Jane. Mezcal has come into its own, gaining increased popularity and more importantly respect on the domestic front and internationally. The 14th annual Feria Nacional del Mezcal (2011), held as always during the second half of July, bore witness to the metamorphosis. The world had finally come to learn that mezcal is often as smooth and complex a spirit as fine single malt scotches, and can be consumed as such. The worm, known as a gusano, is more often than not absent from both bottle and recipe. A Primer on Mezcal in Oaxaca Mezcal in Oaxaca is produced from a number of varieties of agave (often known as maguey), though commercial production utilizes mainly agave espadín. In the traditional method of production the plant is harvested after 8 – 10 years of growth. Its heart, or piña, is baked in an in-ground oven, and then crushed. [While the leaves are not used in the process, they are nevertheless employed in other industries, thus contributing to the reputation of mezcal as a sustainable industry.] The fibrous mash is fermented for up to two weeks, usually in pine vats with water, and nothing else added. Yeasts are naturally produced in the environment. The fermented liquid is then distilled. Mezcal drips from the spigot, usually ready for consumption after a second distillation. Hundreds, if not thousands, of small, hillside and village mezcal producers follow the age-old production method. Some families tell a fascinating history of mezcal production dating back centuries. Most researchers and aficionados believe that distillation was introduced into Mexico subsequent to 1519 by the Spanish. However there are studies which suggest that distillation was practiced by indigenous groups. In addition to these quaint palenques, large industrial multi-million dollar mezcal production factories have come onto the scene over the past 20 years or more. Brands such as Benevá and Zignum exemplify the most commercial mezcal production imaginable. While these facilities also cook, crush, ferment and distill agave, both the means of production and the machinery employed could not be any further removed from the fascinating and often highly ritualistic small-scale production. Commercial producers nevertheless play an important role in disseminating the positives about mezcal and have carved out an important niche in the marketplace. Their advertising and promotional campaigns at least to some extent aid the cause of elevating traditional mezcal to its proper place alongside fine, small-batch whiskeys and other spirits. While it is suggested that their products are perhaps not the spirits one hopes to sample in American or Mexican mezcal tasting rooms, they are nevertheless welcomed and well represented at mezcal fairs and expos. Oaxaca’s Feria Nacional del Mezcal in Historical Context Initially Mexico’s national Feria del Mezcal was a small tasting and promotional exposition. Organizers wisely arranged for it to coincide with the yearly Guelaguetza festivities in Oaxcaca, the last two weeks of July. The Guelaguetza is a celebration of the multiplicity of cultures represented in the state. The mid-summer merriment is filled with unrivalled pageantry and a diversity of dance, costume, music, food and other indicia of the rich cultural traditions for which Oaxaca is known. Hence, at this time of year Oaxaca becomes a Mecca for tourists visiting from all corners of the globe. In the early years the Feria consisted of small booths set up by individual mezcal producers, each offering free samples of at least a couple of different varieties of the spirit. Most palenqueros employed provocatively clad and well made-up young women to lure prospective purchasers towards their stands; sex sells alcohol as much in Mexico as elsewhere. But it’s always been good clean fun and imbibing. However business owners along Calle 5 de Mayo, the street where the kiosks were erected, complained of a little too much rowdiness, especially for the likes of those tourists lodging in nearby higher end hotels. At the same time that mezcal’s star began to rise, organizers started looking for ways to address this concern, and at the same time create an event which would attract a more diverse demographic than previously; both men and women of all ages, residents and tourists alike from a broad range of socio-economic backgrounds. The venue vacillated between a theater and convention center known as Álvaro Carrillo (too far away from the center of downtown to attract the desired crowds), the north end of Oaxaca’s famed pedestrian walkway Macedonio Alcalá (too narrow and restricted in terms of bringing other attractions into the fold), and the largest park in downtown Oaxaca, Paseo Juárez el Llano. In the end, one of its earlier locations, el Llano, won out over the rest. It’s an easy walk from most downtown hotels and guest houses, and a 10 – 15 minute drive from the popular north and east Oaxacan suburbs. It would be the fair’s permanent home. In 2011, for the first time the event occupied the entire two-city-block park. While the number of participating producers did not significantly increase over recent years, the variety of product has, with many more cremas (sweet mezcals) than previously, intended to attract more women (arguably an inaccurate stereotype) as well as others who are not regular spirits drinkers. More aged mezcals from different regions were represented, as were herbal infusions and the odd mezcal made from a different variety of agave. When the Feria was first instituted there was no entrance fee, perhaps contributing to the initial problem. Then a ten peso entry fee was levied in part in an effort to dissuade some attending solely for the purpose of getting free drinks. While it now costs 35 pesos to attend the Feria Nacional del Mezcal, visitors to the festival get much more than their money’s worth; the festival now satiates all the senses. The 14th Annual Feria Nacional del Mezcal in Oaxaca Turns the Corner Outside the Feria del Mezcal and lining its extensive perimeter was a diversity of booths selling virtually every craft produced in the region: alebrijes; tapetes; embroidered blouses, dresses and huipiles; cotton textiles; jewelry and metalwork; hand-turned clay products ranging from terra cotta utilitarian, to decorative black pottery, to ultra-modern high-fired porcelain pieces. Cuisine countered the urge to shop, with tacos al pastor, tlayudas, carnitas, memelitas and more. From the street, the billowing smoke of firewood fueling comals, the rich aromas, and the sizzling of steak arrachera, drew you near – and then inside. Oaxaca is of course known for its gastronomic greatness, so within the confines of the feria the theme continued, with a large sit-down restaurant and booths selling and offering samples of prepared moles and salsas. But you’d come for mezcal, and everything associated with it. A gallery of vintage photos greeted you upon entering: farmers in their fields harvesting agave; traditional roadside facilities; hectare upon hectare of maguey photographed at sundown, at daybreak, in the sun and with shadows. Next there was the media area where passersby were asked if they could be interviewed for TV and radio concerning their thoughts about mezcal and the fair, as well as tourism in Oaxaca. Renowned Oaxacan artists had been contracted to paint oils and water colors, and produce engravings and lithographs, of anything and everything having to do with agave and mezcal, from both cultural and natural perspectives: mezcal as inebriate, and aphrodisiac; agave as a majestic plant standing alone, and being uprooted from mother earth in preparation for its transformation. Artist Emiliano López had one piece in the open air art gallery. Juan Alcázar and Enrique Flores gave printmaking workshops. The grounds were landscaped with outcrops of cactus, agave and other succulents. An enormous 3 – D screen provided the illusion of an expansive field under cultivation, in front of which were real agave, and the tools of the trade; implements, a multi-ton limestone wheel used to crush the baked agave, and a pine vat employed to ferment. Visitors stopped to take photos of their friends and lovers posing as if an actual part of the scene. The massive band shell and stage was host to amateurs vying for prizes for singing, strumming an instrument or telling a story. Local bands played from time to time. Nationally renowned singers and musical groups were given top billing for special evenings: Pablo Montero, María José, Sonora Dinamita, Apuesta and Julion Alvarez. This of course had nothing to do with mezcal, but attracted youth and others who wanted to hear, or just catch a glimpse. And it succeeded, as throngs queued up waiting to enter the fair to see their idols on those dates noted on posters and flyers. But most came to be enticed to saunter up to one makeshift bar as opposed to the next, to sample a blanco, a reposado or an añejo; or perhaps an agave tobalá; or even one of a number of cremas, a rainbow of pastel colored mezcals. There was mezcal for every budget, and for those wanting to spend even more, 1800 pesos for mezcal in a hand-blown glass bottle with a delicate glass sculpture encased inside. Most of the big players were represented, such as stalwart Oro de Oaxaca, several producers from the Chagoya family, and the new rich kid on the block, Zignum. But small palenqueros from outlying villages hours away from Oaxaca, far beyond Matatlán, also came to ply their product. They brought their wives and daughters down from the hills to help, rather than agency hires with simulated smiles, properly poised with sashes over skimpy costumes. Fourteen years after the inaugural Feria Nacional del Mezcal, glamor and glitz still mattered and were a significant draw. According to the Minster of Tourism, this year the fair hosted a remarkable 48,000 visitors. Well After the Feria, Mezcal Marches On But moving forward from 2011 it’s actually the Plain Janes of mezcal which will be the spirit’s best ambassadors, the mezcals made from wild and lesser known varieties of agave, with different flavors and nuances. Hopefully they’ll be better represented at the Feria in years to come. Certainly mezcal still needs its commercial producers, if for no other reason that to use their big budgets to pique consumer interest by providing basic education - there’s much more to mezcal than the worm. As the decade advances and consumers become more sophisticated, aficionados of fine spirits will start to put the Glenmorangies and the Lagavulins back on the shelf, and pick up a bottle of quality mezcal. |

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed