|

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. Dogmatism in the mezcal industry causes misinformation to metastasize. It begins when those with the broadest and loudest platforms create other lesser aficionados, yet still in their likeness. The latter are agave distillate (relative) novices who as a consequence of predominantly online social media find their own audiences, and these neophytes are revered by others with even less mezcal experience. Then they too continue to preach false gospel. And it’s all reinforced; those on the bottom rung are applauded by their disciples above them, and that misinformation keeps climbing until it reaches the top, where those at that pinnacle can applaud their much earlier proclaimed “truths.” Who would ever question the words brought down from Mount Sinai? That would be deemed sacrilegious, tantamount to heresy. There are several manifestations of mezcal dogmatism. Its dissemination ultimately impacts the masses. Change is difficult to achieve once the number of believers increases without a rein to slow it down from a gallop, to a trot, to a walk, and finally a stop. But we must keep on trying to set the record straight, or at minimum be open to receiving differing perspectives, for the long-term benefit of both those who have been lead down the garden path, and the mezcal industry in general. And so, let’s summarize the arguments I have been laying out over the past several years. Wild, Cultivated, Multinationals & Celebrities “Tobalá is a wild agave,” state many in the industry who should know better. Some even label all of their non-espadín agave distillate maguey expressions with the term wild or silvestre. Thankfully change is in the wind, although the breeze blows ever so slowly, even as I and others post photos of row upon row of clearly cultivated barril, tobalá, arroqueño, mexicano, and the list goes on. Yet the misinformation continues. Why? The promoters of such myths try to capture the romanticism of generations long passed, of the poor campesino foraging in the hills. Yes, there is still wild agave out there, and yes, it is being harvested. But certainly not as previously. In my opinion, far more mezcal supposedly produced with wild agave, is in fact distilled with maguey cultivado. Relatively little is produced with the real deal. And that’s a good thing. The uneducated consumer wrongly assumes, or is told, that a mezcal made with wild agave tastes better than its cultivated counterpart, and will often readily pay more. In my opinion quality most often depends predominantly on the skill of the maker. If you visit a palenque, certainly in the state of Oaxaca, sometimes cultivated costs more than wild. That might be because of at least two factors: (1) the carbohydrate content of the maguey silvestre might be higher than that of its seed-grown and transplanted equivalent, thus yield goes up and price accordingly comes down; (2) if it’s been cultivated, that suggests that someone may have paid for the land on which it grows, and has been tending the rows of agave for several years. We know that big business is now in the mezcal industry; over the past decade or longer having purchased outright or an interest in some of our preferred brands. Corporations which come to mind include Pernod Ricard, Bacardi, Diageo and Constellation Brands. They are in the business of making money. And celebrities have their own brands of agave distillate as well. In both cases they have a global reach, meaning that mezcal is now available in countries and otherwise in relatively remote parts of the world where previously the spirit was not on the shelves. And in the case of those movie stars, sports figures and musicians, their name recognition alone increases knowledge of the distillate and accordingly mezcal sales. So there is much more mezcal made with tobalá, tepeztate, madrecuixe, and all the rest, now being sold. And that’s a good thing. Don’t automatically decry the large corporations and celebrity brands. Understand the positive(s) in the case of the former, and that some celebrities endeavor to “do the right thing” when it comes to interacting with palenqueros, their families and their villages. The large corporate interest wants to keep profiting, and therefore so as to continue to do so, want to ensure that these “designer” magueys will always be available to them. They are buying land and having people plant for them; grown from seed, and using the hijuelos, and maguey de quiote. Good or bad, it’s happening. In addition, there are communities, recognizing the mezcal boom, while continuing to allow their residents to harvest from the wild are sometimes requiring that for every wild agave harvested, two must be planted; grown in their greenhouses or on their communal land. And that’s a good thing.[1] What constitutes a cultivated plant? Some say it must have been planted by humans for at least five generations in order to be truly considered cultivated. Otherwise, some say, a more appropriate term is semi-cultivated or semi-wild. But for we as lay people, I would suggest, either of the following defines a cultivated plant, agave or otherwise:

The Purist & Traditional Mezcal “You should only drink traditional, pure unadulterated mezcal,” is an amalgam of what one hears from some working at and owning mezcal bars both in the US, and even in mezcal’s heartland, Mexico’s state of Oaxaca. And it’s also preached by some of the mezcal world’s “purists,” many of whom shun cocktails made with the spirit (but I ask rhetorically if they drink margaritas made with tequila; or are they just anti-cocktail). What do they mean by “traditional” mezcal? I assume they are referring to the agave distillates now categorized as ancestral or artesanal. But do they realize that the mezcal they have been drinking outside of Mexico since the early part of this millennium is not what was most often drunk throughout all of the 1900s (and earlier) and into the first decade of the 2000s? If today you buy your mezcal in New York, London, Vancouver, Paris or LA, you are likely not drinking a traditionally-distilled agave spirit. Why? Because prior to the promulgation and enforcement of the COMERCAM/CRM dictates, there was no requirement to have your mezcal lab-tested for certain chemical compounds or for acidity, or for methanol. Flavor profiles necessarily changed! Methanol contributes to the nature of the distillate just as the head tastes different from the body which tastes different from the tail. All of a sudden, in order to get brands of mezcal out of Mexico, its recipe had to change (unless the producer had already been removing the methanol).[2] So today, if you want to drink traditional mezcal, you must either purchase an agave distillate (as opposed to mezcal) the brand owner of which may not be that concerned with lab test results, or come to Mexico and buy uncertified product directly from the producer, or perhaps drink one of many house “mezcals” (technically agave distillates) offered in local bars, restaurants and mezcalerías. Perhaps you should regularly visit Mexico to buy your agave distillate, if you consider yourself a purist. Many of the same aficionados shun aged mezcal, as well as pechugas, any agave spirit infused with anything (i.e. the gusano, herbs, fruit, etc.), and certainly a mezcal wherein the agave has been steamed in an autoclave or a sealed brick room. They contend it must be baked over firewood and rocks, and fermented in traditional vats whatever that means. They want what they consider to be the real deal. They don’t want the true nuances imparted by the particular sub-species of agave to be masked or adulterated. But wait a minute. Doesn’t the particular type of firewood over which the agave is baked impact (alter) the flavor? Doesn’t the composition of the fermentation vat impact (alter) the nose? Doesn’t the water source (i.e. river, well or mountain stream) impact (alter) the finish? Wouldn’t you get the true nuance imparted by the particular sub-species of agave by steaming it and using stainless steel fermentation vats and a consistent water source filtered the same way all the time? They want traditional, but they aren’t getting it, yet don’t realize it. Mezcal reposado and añejo have been around since long before these pundits were even born, aged agave distillates dating back hundreds of years. And pechugas since likely the 1800s based on archival evidence, and certainly in Oaxaca since the 1930s, if not earlier, based upon oral histories I have taken. How far back must we go for mezcal to be termed “traditional?” And so there’s an incongruity between wanting to promote what they call “traditional” mezcal, and wanting to retain all the natural nuances based on agave type, yet wanting to mask them by cooking over firewood and fermenting in vats made of wood, clay, or animal skin, and using different natural water sources. In a 2021 publication (Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances [Third Expanded Edition with Portraits]), I tried to enumerate the unlimited diversity in nose, body and finish, achieved in traditionally made mezcal. They say don’t drink it with the worm or adulterated with fruit, herbs and/or meat proteins because you’ll then be bastardizing the spirit. But they also say do discern the differences based upon the rest, what they want to illustrate (clay v. copper; growing region, cowhide v. pine vats, etc.), and nothing else. The Best This & The Best That Those at or near the bottom rung of the ladder are now going off on their own tangents, something those near the top never intended to happen. We find them on social media showing their prowess by going as far as commenting in the superlative: “The tepeztate distilled by W palenquero in X village using Y means of production and Z tools of the trade, is the absolute best.” Not only does she lose credibility, but wreaks lasting damage to industry growth. While I disagree with the concept of tasting notes as a general rule in the case of hand-crafted agave distillates, it would be much better to yes, describe nose, body and finish, even with additional descriptors, and leave out it’s “the best.” The problem with superlatives, certainly in this context, is 1) some might not realize that they are essentially subjective, and 2) someone new to the spirit might very well conclude “if that’s the best mezcal has to offer, I’m hightailing it back to single malts.” Epilogue (The Harm Done) As I have noted in Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market and elsewhere, some want to keep mezcal as a secret society for the in-crowd only. That’s what it was like in the late 1990s when the modern era of mezcal began (with Del Maguey et al); at the time it was somewhat understandable. But now the industry has unbridled potential, with an opportunity to positively impact the economy of at least Oaxaca, one of the poorest states in Mexico. Those in the secret society shun the concept of mezcal cocktails despite the fact that their growth in the marketplace helps the economy of Oaxaca and the producers they should want to support. Their dogmatism and spreading of misinformation harms the industry, inhibiting its growth. You know who you are. Take a step back. Act responsibly. Think before you write, speak, promote. Understand that there are very few absolutes in the industry. Let your disciples know others’ points of view and not just your own, and use this to promote healthy discussion. Remember that the longer you’ve been around the industry, the more you will realize how little you know. Alvin Starkman has been gradually increasing his knowledge of mezcal for more than three decades. He has written over 70 articles about the spirit, agave and industry sustainability. Alvin operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (mezcaleducationaltours.com). He is the author of Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances (Third Expanded Edition). [1] As an aside, and not directly related to the theme of this article yet nevertheless worthy of note and discussion at a later date, Schippmann, Leaman & Cunningham wrote: “Demand for a wide variety of wild species is increasing with growth in human needs, numbers and commercial trade. With the increased realization that some wild species are being over-exploited, a number of agencies are recommending that wild species be brought into cultivation systems (BAH 2004; Lambert et al. 1997; WHO 1993). Cultivation can also have conservation impacts, however, and these need to be better understood. Medicinal plant production through cultivation, for example, can reduce the extent to which wild populations are harvested, but it also may lead to environmental degradation and loss of genetic diversity as well as loss of incentives to conserve wild populations.” And so indeed it is a slippery slope. [2] For the average consumer of agave distillates, the methanol in mezcal, even if not removed to meet the standard, will not make you go blind, kill you, or make you gravely ill.

0 Comments

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

Over the past 15 years, perhaps less, there has been a significant change which has gone largely unnoticed, in the self-esteem, psyche, and spirit in distillers and their family members throughout the state of Oaxaca. Visitors who come to Oaxaca for the purpose of sampling and buying mezcal, for learning about the culture of palenqueros and their families, and for a plethora of other reasons, periodically comment on changes observed over the past several years. Things are rather different today from what they experienced on an earlier visit or from what they have been told. But the one profound change is simply not acknowledged, even by those who regularly visit. One of the two differences which does jump out is prices charged for mezcal in the villages near the city of Oaxaca. A dozen years ago a liter of espadín cost as little as 20 pesos, and now it’s upwards of 300 pesos. The other main difference upon which many of the clients of our Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca comment, is in the installations at the palenques: more ovens, stills and fermentation vats; added and up-graded distillation and bottling facilities; relatively modern and/or updated concrete homes where previously much more simple adobe abodes existed; and newer vehicles (while some are still car-less). That’s all fine, and certainly welcomed by the families of palenqueros, but it’s merely “stuff.” A much more important change has begun to take hold, and it’s rather apparent. Material possessions can do only so much for the soul of a people. Prior to the mid-1990s’ commencement of what I term the modern era of mezcal, very few people were interested in the agave distillate. In the US that gut-wrenching hooch was drunk mainly in shots, by youths who couldn´t afford anything better, with all manner of myth about who gets the worm. In urban Mexico it was shunned, a drink for poor village folk. Then the pilgrimage began. Along with those wanting to learn, buy and sample, came the rest; the entrepreneurs interested in starting their own brands, the professional photographers, the documentary film makers and other media sorts. And so a transformation began, not merely bringing more revenue into family coffers, but something much more profound and “needed,” I would suggest; a dramatic change in the self-esteem and sense of self-worth of the palenqueros, their partners, sons, daughters, parents and grandparents. Although my introduction to the world of mezcal began with my travels to the state in the late 1960s, I must confess that my memory of visits to palenques and to the homes of the makers of mezcal is vague at best. But my witnessing of the noted metamorphosis, beginning in the early 1990s, does indeed afford me an opportunity to comment on change ushered in which began in earnest with the beginning of mezcal’s modern era. In previous years, palenqueros and their family members were extremely meek, modest, and at times interacting with visitors from abroad with literally their heads bowed down. It was as if they were close to being embarrassed about what they did for a living; “try it, I have two or three kinds of mezcal which might interest you.” Not now! Today there’s a rather discernable sense of self-pride in their craft, in how they make their distillate. Even without a request being made they are anxious to illustrate each stage of production. There is a sense of self-worth, and confidence that you will want to learn from them and have them and their partners and their children have you sample their mezcal. Of course, each distiller wants to make a sale. But now there’s something more, in their affect, in their interactions with those from outside of their world. Heads are now high, smiles peak through, “come and let me show you this.” If you buy, that’s great, but if not, the palenquero has nevertheless obtained something equally if not more important to him and his family members, a shot in the arm of self-respect, dignity, and sense of worth which money cannot buy. And now, when the photographer shows up at the palenque, there’s no longer the retort that he doesn’t want his soul to be stolen. He wants to be pictured online and in magazines. He wants to be one of the subjects in a documentary. I personally detect the pride, the enthusiasm, the courageousness, all shining through at every turn; perhaps not as much when interacting with middle class urban Mexicans who in recent memory would not even venture into the villages beyond just passing through along a highway to somewhere else. But still, even then, there’s a glimmer of difference in self-image, as if to say “now what do you think about what I do.” And so come for a visit to rural Oaxaca armed with cameras and video equipment. Don’t feel like you are intruding into their worlds and will be perceived as mere gawkers; nor embarrassed that you might not buy enough or any at all. Understand that you’re doing your part to help the palenquero and his family. Money buys a little, but more importantly, sampling agave distillates from the source is like serving chicken soup … it’s good for the soul. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). He and Spike Mafford, photographer, collaborated on the recently published book, Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances, Third Expanded Edition with Portraits. When You Purchase an Agave Distillate, What Do You Consider Aside From Price, Nose, Flavor & Finish?6/5/2022 Selecting what brand or expression of mezcal to buy should be determined by more than considering price and your own or published tasting notes. Of course they will form part of the equation, but so should your knowledge and understanding of to what extent, if any, the brand owner is giving back to the community.

What is your favorite brand of mezcal doing, if anything, to support the local economy of the town or village where the agave distillate is being produced, beyond simply purchasing from the palenquero? Does it donate to Mexican charities, and if so to what extent? Some brands do the right thing, believe it or not even some of those owned by celebrities. Over the past decade, several times a week I meet various mezcal novices and aficionados. I can perhaps count on one hand the number of times anyone has mentioned a brand giving back to either the local or broader Mexican community. The discussion the spirit imbiber begins is virtually always about nose body and finish, and/or value. Sometimes there is the odd commentary about the multi-nationals’ or movie/sports stars’ incursion into the industry. Brand owner personality lies along a continuum. At one end are those motivated by strictly altruism (to the extent it can ever exist at 100%), and at the other are those concerned with profit and little if anything else. I suspect that a fair number lie towards or even hug the latter, while nary a single one is to be found at the former. But being in a capitalist society suggests it’s okay to make improving one’s brand’s bottom line rather important. But that doesn’t mean we should willy-nilly accept brands which do their best to buy bulk agave distillate for as cheap as possible, even if part of the motivation is to benefit the end consumer. And we should reject those who do not give back to one or more segments of the community in need, by not supporting those brands nor singing their praise, no matter what the quality of the various expressions. If you want to continue to witness the industry thrive, that is those brands producing ancestral and artesanal mezcal, investigate before making a purchase, or promoting on social media or via any other means. You’ll feel better about yourself. Red flags should go up, at least provisionally, regarding a product seemingly under-priced, just as for the mezcal appearing to be over-priced. Does $25 USD for an espadín at 45% ABV a bottle of 750 ml suggest the brand is squeezing the palenquero as much as possible to get the best price? Does $60 USD suggest the brand is paying a lot and at the same time donating to a worthy charitable cause? Perhaps the brand is even partnering with the palenquero, which at least to some extent removes that inequality of bargaining power. The imbalance is evidenced by a brand owner knowing that the producer is in dire need of sales and thus he has the upper hand in negotiating price. The two as partners, on the other hand, suggests that as the brand flourishes in the marketplace, so does the economic lot of the palenquero. So what should you do before buying? What do I mean by “investigate?” We can begin a groundswell in the industry, as long as we do our part. Admittedly, it may require that you depart from your comfort zone. At the Retail Level When you go to your local wine and spirits store or mezcalería, ask the salesperson or better yet manager if the brand gives to charity or does anything else to support the state or community where the mezcal is being distilled. The answer will likely be “I don’t know.” Follow up by asking the person to contact the distributor to find out. Now many brands, for good reason, do not promote their charitable endeavors, but once asked should readily explain with details. Often the distributor does not know although he should so as to enable him to better promote the brand. It’s simple to give out your cel number and ask to be called once the vendor has an answer for you. But walk out of the store without buying! The next retail outlet you attend might have the answers you should be seeking. At the Trade Shows & Tasting Events At the trade shows, spirits competitions and tasting events conducted by brand owners or third parties it should be easier to get the answers you want. If not, then there’s a problem. Those promoting particular brands should be armed with a lot of information beyond telling you how great their products are and a little about the family which produces the spirit. When you are then told about the mountain of revenue the palenquero is given in reply to your query, remember that the members of his family are the ones awaking at 4 am to harvest and staying up all night to distill; not the brand owner who lives a much more comfortable lifestyle. And if you are told about how many hands the mezcal must touch before landing in a bar, store or mezcalería (i.e the Three Tier system in the US), and thus that the brand owner makes very little, that is simply a way to avoid answering your pointed question. You might even want to ask about any belief in tithing, and have a fruitful discussion about the practice as it relates to the business of mezcal production and sales. At both of the two foregoing levels you should press for details. Get the name of the charity, the address of the school the brand rep states it built, or water filtration plant it constructed for the entire community. Ask if there is a partnership agreement between the palenquero and the brand as opposed to simply an agreement fixing price per liter for the term of the contract. Brand websites and Facebook or other online mediums might provide the information outlining the information you should be seeking. But as suggested earlier, many brands might be uncomfortable promoting their charitable giving. But some are not. Several brand owners over the past few years have in fact asked me where they should park some of their profits in order to help the state of Oaxaca. Epiloque Do your research. Be just as critical as you are of brands of clothing, shoes and widgets which profit from the cheap labor encountered in third world or developing nation sweatshops. Help the agave distillate companies operating towards the ultra-capitalist end of the continuum to understand that making their charitable nature known to the public will ultimately cause profits to spike as consumers come to understand that buying the brand is a good thing. Quality of product will remain important, and price paid will diminish as a determining factor. Or, assist brands to rethink their business practices in order to then assist the palenqueros a bit more than is presently the case. I am not suggesting that donating to charities or partnering with the palenquero is the only way to help, nor that and one or both should be a prerequisite for supporting a brand. There are umpteen ways. And it’s not only the brand owners who should be encouraged or even shamed into “doing the right thing;” rather every person or business along the chain making a profit. They should understand that perhaps helping to grow the industry at large is just not enough; especially here in Oaxaca, one of the poorest states in all Mexico. Alvin Gary Starkman (M.A., J.D.) is the author of the recently published third edition of Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances. He operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (mezcaleducationaltours.com). Alvin Starkman, MA., J.D.

Who better to write a book about the business of mezcal than a Oaxacan lawyer who specializes in advising palenqueros, brand owners and prospective agave distillate entrepreneurs, about the quagmire of industry rules, regulations and nuances? In El ABC del Negocio del Mezcal [Carteles Editores, 2021], Blanca Esther Salvador Martínez accomplishes that end in spades. And who better to put mezcal in its historical and global context than an academic who teaches a class centering upon international marketing? Maestra Salvador Martínez does that as well. Translated as “The ABCs of the Mezcal Business,” the book is an easy yet detailed read, even for those of us who are not 100% fluent in Spanish. The 100-page publication consists of four well-footnoted chapters, in addition to a preface, introduction, epilogue, glossary and bibliography. The author breaks it all down into close to 90 headings plus charts and diagrams, thus making every point she endeavors to convey relatively simple to digest. And for those wanting to delve further into the subject matter, even the references are categorized; into legislation, books and related documents, websites, and journalistic coverage. Ms. Salvador Martínez’s initial chapter contextualizes mezcal as a unique spirit by explaining the development and importance of the DO [Denominación de Origen]. Her Roquefort cheese analogy hits home. She then answers those who would be critical of the concept of the NOM [Norma Oficial Mexicana]. The chapter dealing with concerns within the industry is extremely thorough. But it would be wrong to assume that the issues the author identifies are restricted solely to this section of the book. Indeed the problems and pitfalls are woven throughout the remainder of the treatise. Those subsequent chapters primarily address (1) action steps reasonably required as prerequisites for entering the industry, and (2) practical advice. The book canvases the vagaries of agave production based on:

The mezcal industry is complex. The roadblocks which potentially preclude entry and certainly delay, are numerous. Ms. Salvador Martínez stresses, as a cautionary note, the importance of seeking out different individuals, each an expert in his/her field, rather than adopting a one-stop-shopping attitude when it comes to relying on the advice of others. She quotes Albert Einstein as stating “a smart person resolves a problem, a wise person avoids it.” Ms. Salvador Martínez accurately pinpoints and explores the barriers to embarking upon a successful business plan, together with resolution mechanisms. However for me it was the ethical dimension which receives comprehensive treatment which most drew my attention. She identifies what I refer to as an inequality of bargaining power to which we all must be cognizant and find a way to reasonably and fairly address. For the pure imbiber, whether novice or aficionado, the book it important because to a certain extent it is a primer which covers some of those basics in a readable to-the-point fashion. They are the tidbits which are not readily discernable from other literature about mezcal, or from attending a bar or mezcalería and inquiring of those who at first blush appear be in the know. And to be clear, El ABC del Negocio del Mezcal is a book for more than those contemplating or in the process of getting into the industry. It should also be read by those already integrally involved with the business of mezcal. It encourages the reader to take a step back and re-evaluate why the desire to be or remain in the industry. In order to truly respect mezcal and all those involved in its production from field to bottle, there must be an impetus beyond the spirit as simply a vehicle by which to earn income. And so for all, this book is a must read; once, and again as a refresher. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca [http://www.mezcaleducationaltours.com]. As part of his mission, he counsels clients on several of the dimensions explored in Ms. Salvador Martínez’s book. Alvin Gary Starkman, M.A., J.D.

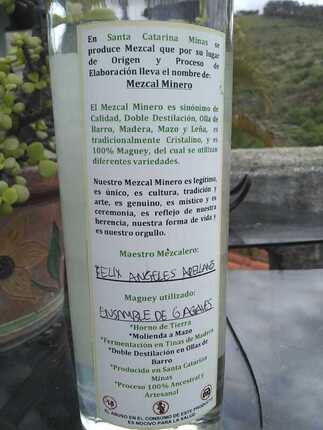

One distills ancestral mezcal, while the other makes the more traditional artesanal (artisanal) spirit. They live and work in different districts of the state of Oaxaca, and their generational backgrounds, personalities and lifestyles are rather different. But a common thread which binds is that they have never allowed family distillation methods to constrain them. They think somewhat outside-of-the-box, albeit in divergent manners. And in so doing each in his own way improves efficiency. This article presupposes that the reader either (a) has been to Oaxaca and seen both types of palenques in operation and understands the broad strokes of how they typically function, or (b) has read and/or seen enough videos or documentaries to understand how each of ancestral clay pot distillation and artesanal copper alembic production works; and their distillery configurations. While of course the palenques of Jose Alberto Pablo and Rodolfo López Sosa are not entirely unique, each does significantly deviate from what continues to be the village norm. One might say that each distills to a different drummer. José Alberto Pablo, Zimatlán District of Oaxaca José Alberto Pablo hails from a village in Oaxaca’s Zimatlán district, namely San Bernardo Mixtepec, where for generations tradition has dictated, and still does today, condensing in laminated metal as opposed to copper or stainless steel. The result is a mezcal which is amber in color, caused by the rust which forms on the laminate. However, Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM), the main regulatory board for this agave distillate, will not certify his mezcal because of the chemical compounds detected in laboratory testing. If he continues to produce the mezcal his fellow villagers demand, with the rust, he cannot sell that mezcal as certified. And so now on the cusp of certification, José Alberto still relying on sales to locals continues to use laminate, but also employs both stainless and copper condensers. He prefers the taste produced when using the stainless. He switches between the two as he wishes, but his staple remains an agave distillate produced using a laminated metal condenser. And over time, given that “rust never sleeps,” his traditional mezcal takes on an even deeper tone, eventually arriving at orange, after which time as a consequence of use a new condenser must be employed. But the more significant uniqueness of José Alberto’s operation is found elsewhere. Fermenting in clay pots is not particularly unusual. However while others in his village keep their ollas de barro outdoors, this young maestro constructed a room in which the fermentation pots are situate. They are still exposed to the airborne yeasts of the area, but José Alberto has a distinct advantage over his fellow palenqueros. Not only does the tepache (mash of liquid and fiber) heat up quicker indoors than if the pots were outside, but the fermentation process occurs faster also because the roof material allows the sun to partially penetrate, particularly important during the cold weather months. And during the rainy season he doesn’t have to cover the pots as other villagers do. While José Alberto’s still configuration and apparatus have a couple of small unassuming yet unique designed features, two characteristics are particularly noteworthy: (1) similar to more sophisticated operations, he recirculates the water used to condense with the aid of an energy efficient pump and a brick and concrete constructed water tank …. as opposed to directing the water into a stream or otherwise discarding and thus arguably wasting it by enabling it to enter the water table; (2) his three stills are fueled by one firewood aperture which singularly heats the triumvirate of ollas. When the ollas are distilling at different stages he is able to simply move around the logs as he wishes. Rodolfo López Sosa, Tlacolula District of Oaxaca Rodolfo López Sosa’s wife thought he had succumbed to premature senility when he told her he wanted to build his palenque not close to the shore of the river running through his village of San Juan del Río as his fellow distillers had done, but rather high up in the mountains overlooking the residential and commercial area far down below. He draws his water from a spring water source even much higher up from his palenque. The airborne yeasts are indeed different at his palenque, but the more significant feature is the water quality, distinct from that sourced by the rest of the mezcal producers the majority of whom draw the lifeblood of production from the river or a shore well. The recently retired teacher, now alcalde (chief judicial officer or magistrate) of the village, is similar to José Alberto in that he does not assume that the way his forebears have done things and his father has taught is necessarily the best way. Naturally some courses of action should not be trampled. One is the type of maguey (agave) used to distill. The microclimate is highly suited to growing Agave angustifolia Haw (espadín). [In José Alberto’s case it’s lumbre.] So while Rodolfo occasionally sources maguey from further afield as do others, his preference is to stick to espadín. So how does he achieve an assortment of aromas, flavor profiles and finishes, if not via aging in oak? Rodolfo has a knack for achieving diversity by distilling with a variety of different fruits, herbs and other products of nature during the second pass-through, that is when distilling the shishe. Ah, but you say he’s just making a vegan pechuga. No, and in fact when he does a third distillation for his pechugas, he often uses only turkey breast with nary a fruit or herb, or adds a very limited number of additional ingredients. This is distinct from, for example, the traditional recipes employed in towns and villages such as Santa Catarina Minas, San Baltazar Chichicapam and Santiago Matatlán. And when he does add something foreign to the still, typically it is a single additional ingredient. Rejecting the usual cacophony of flavors emerging from a pechuga in favor of using only one or two external ingredients results in a more subtle agave distillate with only a hint of what he adds emerging. Rodolfo and I are ad idem when it comes to the result we seek to achieve in our distillates, and so for those two (and other) reasons, when I consider a particular recipe, he’s my go-to palenquero to bring it to fruition. Question: How does one avoid the arduous task of removing the rocks from the oven before commencing the next bake? Answer: By not removing the rocks. In Rodolfo’s world, the mound of rocks is permanently placed on a platform which includes special order clay bricks. At the back of his oven, there’s a staircase leading downwards, to a brick and mud wall, the other side of which is where the firewood is inserted under the platform. And so just prior to the subsequent bake, in the course of 10 – 15 minutes Rodolfo takes apart the wall, then removes the charcoal if he so desires, places fresh firewood, and again taking no more than 15 or so minutes seals the wall with the bricks and mortar. Why most others do not adapt what Newton has taught is not germane to this essay. But how Rodolfo has done so certainly is. In the usual course of crushing, once the horse, mule or team of oxen has finished, one pitches the bazago into a wheelbarrow, walks it up a plank of lumber and then dumps it into a wooden fermentation vat, or worse, alone or with someone’s assistance lifts the wheelbarrow and them dumps the contents. Then at the end of the day’s crushing and lugging, the accumulated liquid is swept into a depression, gathered into a pot and finally emptied into the vat containing the bagazo. Alas Rodolfo’s method stands in stark contrast. Rodolfo’s tahona on the circular encasing is only a couple of feet from a door leading to a lower level where his vats are located. A fermentation vat is slid to and right under the door entrance. The bazazo is pitched directly into the vat, then once filled the vat is moved aside and another is rolled to the location of the first. No wheelbarrow, no ramp, no lifting, simply gravity. There is a small hole in the stone encasing in front of the door leading to the vat area. The hole is dug down and through the wall up to which and opening to where the vat is located. And so at the end of the day the accumulated liquid is simply swept into the hole and it drips directly into the vat. Once again, it’s all gravity! I’m not sure if Rodolfo was recently awoken yet again, perhaps this time by an apple falling on him from a tree, or perhaps it was merely a natural development in the course of teaching his former students. But he’s taken another lesson from Sir Isaac. In order for tractor trailers to access his palenque to transport pallets of bottled and boxed mezcal to Oaxaca and then to the border, a port, or to other domestic destinations, they must wend up an extremely steep dirt roadway and then somehow make a sharp left turn. It’s only a 70 or so yard exercise, but a daunting task. And so this palenquero extraordinaire plans to build a conveyer belt to lower the pallets to the main roadway so that the tractor trailer driver need not worry about getting stuck, or worse yet toppling over the cliff. Both Rodolfo and the younger José Alberto continue to innovate, their only constraint being insufficient revenue derived from mezcal sales for the realization of their evolving ideas. But no doubt over the ensuring years there will be more to come which distinguishes each of them from their fellow Oaxacan palenqueros. Mr. Starkman with his associate Randall Stockton operate Mezcal Educational Tours of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationalexcursions.com). Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

The allegations come to the fore within the context of remarks of some mezcal commentators. They assert that “foreigners” who own brands of the agave distillate are guilty of cultural appropriation. Of course, the few are far from being the great thinkers of our generation, though they do get some traction; thankfully only from those who similarly fail to carefully if at all delve below the surface. All that can be done to combat the oft erroneous charge is to take steps to do the right thing: strike a balance between advancing one’s entrepreneurial tendencies on the one hand (if you don’t like capitalism, then move), and on the other, openly helping the mezcal brand owner’s palenquero associates, their families and their communities. One must go beyond buying mezcal for resale and having villagers bottle, label and pallet. That is not enough. Many brand owners do indeed work towards and in fact achieve altruistic goals, but do not, I suppose to their credit, advertise what they do. Perhaps that should change if for no other reason than to keep the naysayers in their Neolithic caves. This musing addresses primarily readers who are considering starting their own brands, and those with existing brands who may want to do a little better for their Mexican palenquero brethren. This would go a long way to quieting the holier than thou out there. But first we should all acknowledge that Mexican and foreign-owned brands should probably be lumped together. In both cases there is generally an inequality of bargaining power; think about it for a moment! Yes, the imbalance can easily be redressed, if the motivation exists. Palenqueros are doing their part to react to the problem, if not by design then by default. They are using their new-found wealth to advance the education of their progeny through entry into university degree programs. This in turn leads to a different, more critical way of thinking, or perceiving the world and its players. Many of these young lawyers and engineers remain in the villages of their parents, assisting in whatever way they can given their new-found worldview. But that’s a baby step. Something more is needed right now since we don’t know what 20 years hence will mean for the industry. Consumers are fickle, especially in the world of alcohol. How do the rest of us eschew the notion of exploitation? Us? Yes, even those without an ownership interest in a brand of agave distillate, but who are somehow benefiting from the mezcal boom. Here’s how, addressing both prospective and existing brand owners, and yes to some extent the rest of us:

Giving enhances our own self-esteem. But you’re reading this not to support feeling good about what you are already doing, but to consider doing more. And of course to confidently dismiss all those who would be critical. We’ve already bolstered the self-esteem of palenqueros, arguably something very tangible. But is that enough? Whatever you decide to undertake, consider letting the world know, even though doing so may run contrary to your best judgment regarding maintaining humility and a low profile. How else can we shout them out and proclaim “we’re doing more than enough; what are you doing?” Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). In the course of leading agave distillate tours of ancestral and artesanal operations, he will not hesitate to call out those he perceives and taking financial advantage of the imbalance of bargaining power in their favor. Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. Within the first couple of hours of leading a Oaxacan mezcal educational tour, two of the most commonly asked questions are, “what’s the difference between a mezcal ensamble, a mezcla and a blend,” and, “why do the palenqueros do mixes in the first place.” In this article I do my best to answer both questions, based on having been around agave distillates primarily in the state of Oaxaca for the past 30 years, and on a very frequent basis over the past couple of decades having spoken with tens of traditional distillers and their family members (who produce mezcal ancestral or artesanal) regarding such queries. Mezcal: An Ensamble, a Mezcla, or a Blend Many mezcal aficionados nonchalantly toss about the word “blend,” such as stating “oh, so it’s a blend of tobalá, madrecuixe and espadín.” There is certainly debate and disagreement amongst both the mezcal geeks/experts and the distillers (even from the same village) regarding nomenclature when it comes to mixing different species and sub-species to arrive at a desired end product. But there is, or at least in my opinion should be, a consensus distinguishing a blend on the one hand, from a mezcla/ensamble on the other. Blends are commonplace in the world of mezcal, but typically not in the world of artesanal or ancestral production. Think of a blended whisky. Take two or more finished products, blend them together, and you get, for example, Johnny Walker Red Label, a blended whisky (as opposed to a single malt). Now switch to agave distillates produced in the large modern factories in Oaxaca such as those en route to San Pablo Villa de Mitla or on the outskirts of Santiago Matatlán, just to name a couple of locales. These factories can and do buy large quantities of distillates from various sources, bring them to a central facility, blend them, and voilá we have blended mezcals. Or they can produce different batches at the same distillery, and then blend them together. The foregoing is an easy way to distinguish a blended mezcal from the others, regardless of whether we term them ensambles or mezclas. Now think of the mezcals commercially available through retailers in the US, Canada, the UK, and elsewhere around the globe. The labels typically include the word “ensamble” to identify a mezcal made from two or more distinct varietals of agave. Usually the piñas have been baked together, then crushed together and placed in a fermentation vessel, and finally the mosto as it’s known, is distilled. Thus, the mixing starts at the beginning rather than at the end. A variation on the theme is baking in different lots and/or the agave at different times, but then crushing and the rest, together. But some palenqueros state that the broad means of production should properly be termed a mezcla rather than an ensamble. And so the disagreement remains, and will likely continue into the relatively distant future. A few of my palenquero friends steadfastly maintain that it’s a mezcla when the mixing starts at the beginning, and an ensamble is what we (should) refer to as a blend. But what happens when those same palenqueros’ distillates are bottled, labelled and shipped abroad? The label pretty much invariably states “ensamble.” Why, one might ask, is there is such groundswell of disagreement between the two camps? Many of those imbibers in the English (and I suppose French) speaking world know the word “ensamble” but not the Spanish word “mezcla.” The word “blend” would never be used since to many it has a less than quality-product connotation. And so on the store shelf we find mezcal ensambles, and typically not mezclas. In my opinion we can use the words mezcla and ensamble interchangeably, just as tow-MAY-tow and tow-MAH-tow. Don’t get hung up on something akin to that which etymologists often disagree concerning. But do recognize the difference between blends on the one hand, and mezclas/ensambles on the other. Top Five Reasons Palenqueros Mix Different Varietals of Agave !. Several years ago a client asked one of my palenquera friends how she determined how much of each species she mixed together to arrive at her ensamble of six agaves. Her answer was rather simple, easy to understand and made an abundance of sense: “we brought one donkey-load of each type of agave to the palenque, and that’s how we decided.” Before the modern era of mezcal, which dates to no earlier than the mid-1990s more or less, foraging was the order of the day, and often regardless of what kind of agave was put in the oven and further processed, the end product was called just plain mezcal: not madrecuixe, nor tobalá; termed neither an ensamble or a mezcla. That’s what mezcal used to be. I recently purchased 10 liters from a neighbor who hails from a far-off village, some six hours away from the city of Oaxaca. Here in the state capital, specifically in our neighborhood, he flogs his villagers’ honey, coffee, and mezcal distilled in clay. He described the mezcal as made from maguey campestre, that is, agave from the countryside. It was just plain mezcal, produced as has been the case dating back hundreds if not thousands of years. There are still palenqueros who harvest whatever they can, from wherever they can, in as large quantities as time, distance and beast of burden allow. But these palenqueros are in the minority, rarely encountered by our readers, except those who want true far-off adventures to where one never knows what will be sourced; with what species of agave the purchase has been comprised. 2. The polar opposite of 1. above, is when a palenquero combines different types of agave because the ultimate taste is extremely agreeable to him. The corollary also sometimes comes into play. That is, he will refrain from mixing certain varietals together because the combination does not yield a good flavor. Typically, nose and finish do not enter the equation; taste rules. 3. The objective of many palenqeros is to completely fill as many fermentation vats as are to be used for the particular oven-load of baked, sweet, crushed agave. Often roughly a ton of the mash fills a wooden slat vat. While all is based on science, it is an art, a skill, which doesn’t always work out as planned. Sometimes, for example, eight tons of agave, one ton of each varietal, are baked together, then segregated with a plan to ferment one ton of each in a particular vat. But occasionally there is a bit left over from a couple of the species; the extra won’t fit into the vats for which each sub-species has been earmarked; That is, without seriously overflowing once water has been added and fermention begins in earnest. And so the palenquero will combine the excess kilos together into a vat, resulting in a particular mezcla which may never be repeated; unless of course it yields a particularly agreeable ensamble. 4. Sometimes a palenquero will combine two species of agave, in circumstances wherein one has a low sugar content, and the other much higher. The motivation is that this may result in a higher yield of the ultimate mezcal. 5. Finally, at least one palenquera friend is rather sensitive to what she is compelled to charge for mezcal produced from a particular varietal of agave, based on typical yield. She has explained to me that a mezcla sometimes is produced in a way that reduces the ultimate cost she must charge, yet retains much of the flavor of the more expensive (low carbohydrate content) type of agave. She used the example of combining tepeztate with some espadín in such a way that the end product still has a classic tepeztate taste, yet is not as expensive as it would have to be if she were to distill 100% tepeztate. So there you have it, my take on nomenclature, and what I have gleaned to date as to some of the reasons ensambles of mezcal and agave distillates are produced in the state of Oaxaca.

Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. How can we determine if our preferred brand of mescal is properly termed a craft spirit? In this opinion piece I attempt to refrain from using brand names of mezcals and agave distillates we tend to consider being traditionally produced (i.e. ancestral or artesanal). The reader, after reviewing the following, will likely be able to place particular mezcals along a craft spirit continuum. And so right off the bat my thinking about the topic should be clear, that is at least my singular broad conclusion. Arguably the most primitive of agave distillate operations this century. Understanding and defining craft spirits is a complex topic with several nuances and points of view, even for those in the know. Adding mezcal to the mix further complicates, and makes arriving at concrete answers even more dumbfounding. Craft Spirit Definitions A search for a clear definition of “craft” within the context of spirits yields many results. Typically it denotes drink made in a traditional or non-mechanized way by an individual or a small company, or made using traditional methods by small companies or companies and people that fashion it. This alone reveals problems which arise within the mezcal context, when one tries to define “traditional,” “non-mechanized” and “small.” When the word “craft” is used as a verb, we fine definitions such as “to make with care or ingenuity,” and “to exercise skill in making, typically by hand.” Again there are issues when parsing the phrases to determine their applicability and relevance to mezcal. The community of the American Crafts Spirits Association (ACSA) has different definitions of “craft,” and thus has elected to not live by a singular definition, but rather to allow its members to each come up with an interpretation which serves his/her needs. However it has indeed passed judgment on what it considers to be subsumed by the term “craft spirits,” and what it considers to be a “craft distillery.” And so ACSA believes that: Craft Spirits means (1) a product made by a distillery which values the importance of transparency in distilling, and remains forthcoming regarding the spirit’s ingredients, distilling location, and aging and bottling process, (2) a distilled spirit produced by a distillery producing fewer than 750,000 gallons annually, and (3) no more than 50% of the Distilled Spirits Plant (DSP) is owned directly or indirectly by a producer of distilled spirits whose combined annual production of distilled spirits from all sources exceeds 750,000 proof gallons removed from bond. A craft distillery is a facility which values the importance of transparency in distilling and remains forthcoming regarding its use of ingredients, its distilling location and process, and aging process. It produces less than 750,000 gallons annually. It directly or indirectly holds an ownership interest of 50% ownership or more of the DSP. The American Distilling Institute (ADI) is another industry organization. It provides a craft spirit certification designation. For ADI to certify:

The most sophisticated of mezcal distilleries, the polar opposite of craft. Factors to Consider Based on the foregoing, as well as from a review of several articles centering upon applicable definitions, it is fairly easy to conclude that within the mezcal context a simple answer should not reasonably be proffered, because of the lack of uniformity in the agave distillate industry; perhaps arguably distinct from, for example, the single malt scotch pursuit. However we can examine a number of factors and reach our own conclusions, both regarding our favorite brands of mezcal, and the spirit in general:

Emptying a copper mezcal alembic in San Lorenzo Albarradas, Oaxaca Discussion Within the Mezcal Context Ownership of Brand / Distillery: Should percentage or type of ownership of the distillery be a factor in designating a mezcal brand as a craft spirit? Perhaps instead we should examine control of means of production. We know that Diageo, Pernod Ricard, Samson & Surrey and Bacardi are all in the mezcal business. If the distillery proper is still owned by the family of palenqueros, but decisions are made by the conglomerate, how does that change our thinking? How “hands-on” can the family be, other than participating in all processes, if its members are excluded from the decision-making process? Ownership of a brand by a multi-national corporation should not be the determining factor. In many cases sale to one of the big boys simply enables the brand to achieve global exposure than it otherwise would not have enjoyed, a good thing in terms of helping the family of palenqueros, the community, promotion for the region, etc. But once the non-Mexican corporate entity begins to tamper with means of production and tools of the trade, then the other factors come into play. If the corporation, let’s say Pernod Ricard, has purchased 100% of the brand from the previous owner(s), but leaves day-to-day management to them, can the brand still maintain a craft spirit status? Samson & Surrey actually boasts its “craft spirits portfolio” and advantageousness of having the “resources of a larger company.” It appears to be doing all the right things. Its reference to “human touch” would bring its products into the fold of “craft,” noted above as in “with care.” Let’s examine Mezcal Benevá, a brand which most would likely agree does not produce a craft spirit, even though over the past couple of years it has added equipment to bring some of its production under the rubric of the term artesanal. The brand is 100% privately owned by a Oaxacan family (the last time I spoke with ownership), some of the members of which have a strong pedigree of production dating back generations. Its annual production is less than 750,000 gallons, but sales are more than 100,000 gallons. It lacks transparency only to the extent that, to my knowledge it does not offer access to its plant by the general public; otherwise in my opinion it is transparent in all determinative respects. The main issue with Benevá is means of production and tools of the trade, employing computer technology and finely calibrated scientific equipment, with its autoclaves, stainless steel equipment, diesel fuel and the rest. How different is Benevá from Lagavulin single malt scotch, owned by Diageo? Would you consider Lagavulin a craft spirit? Diageo is a publically traded company. This brings us to “values.” Is the first priority of a company which trades on the stock market to answer to its shareholders (i.e. improve bottom line above all else; of course I’m not referring to “green” companies)? If so, then where do its values lie? Do we put Diageo in the same category as Benevá, both as non-craft enterprises? Lagavulin appears to maintain tradition, but produces well over 100,000 gallons annually, and I would suggest at the end of the day must answer to its parent company. Equipment Employed / Production Methods: If a mezcal brand has several distilleries producing for it, using traditional, non-mechanized production methods and tools, but produces one million gallons annually, is it still producing a craft spirit? If one of the brand’s products is a “blend” in the whisky sense, that is, not a traditionally made mezcal, should we refrain from terming the blend a craft spirit? What if a palenquero elects to use a gas powered crushing machine rather than mashing by hand or with horse and tahona, just to make like a bit easier for him? Is it no longer “craft” because the product arguably does not fit within the definition of “traditional” or “non-mechanized?” What if the palenquero switches to an autoclave for one or more reasons, including wanting to:

Volume Produced: I have already touched upon the volume of production index. I don’t think that volume should be a factor, at all, if it is clear from an examination of all the other determinants whether the brand or the distillery is craft, or not. If we cannot pigeonhole by looking at the rest, then, and only then, perhaps an examination of volume produced can correctly sway us in one direction or the other. Or, using the continuum model, take us closer to one end versus the other. Staff Numbers and Relationship to Owner(s): This, once again, should be one of the lesser important factors in making the craft spirit determination. Staff numbers reflects success of the brand and little if anything more, which returns us to numbers (i.e. gallons produced). What is the maximum staff numbers allowed for the brand, or distillery production team, to be considered craft? Returning to Benevá, the Zignum brand is just down the road, but owned, to my recollection, by non-Oaxacans or at minimum non individuals whose families emanate from nearby mezcal producing villages. Yes the two are large sophisticated operations, and likely each has a comparable number of employees. But in the case of Benevá, likely most are family simply because in a general rural Oaxacan sense, owners tend to prefer hiring family whenever practicable. The Zignum ownership likely hires workers who are not family because ownership is comprised of “outsiders.” So as relative to Zignum, Benevá can boast at least one half of this craft dimension, that is, the strength of family relationships from top to bottom. But certainly this does not mean that Benevá is a craft spirit. After the mezcal bake; tasting a piece of baked agave to ensure sweetness is okay. Transparency and Values: Should the consumer always be able to readily learn the name of the distiller and location of the distillery? There are typically reasons for withholding this information. The reader can judge for herself the validity, and the extent to which this should impact her thoughts about whether or not the mezcal should still be considered craft. Reasons include:

Where I think a mezcal’s characterization should be impacted, is regarding misrepresentation of the contents of the bottle. And regretfully this does occur. There are brands of traditionally-made mezcal which label every bottle, except those distilled with espadín, as being made with wild agave; wild tobalá, wild madrecuixe, wild mexicano, and all the rest. Now yes of course there are still wild agaves up in the hills and otherwise far off, but currently virtually every agave currently used to produce mezcal in the state of Oaxaca is under cultivation. How could the Diageos and the Pernod Ricards of the world, each with a global reach, meet demand if they were not having these species cultivated for them. A good friend of mine has 16 different varietals under cultivation, only one being espadín. Yes there is literature stating that only after the fifth generation of production, should one begin to classify the plant as cultivated. But how does the public know? The better and more honest route is to label “semi-wild” or “semi-cultivated,” or not preface the name of the species with anything. Not following this suggestion illustrates a significant lack of transparency. But thankfully the good and the righteous outweigh the bad and the scoundrels. It all comes down to the values the brand and the palenque embrace. If profit is first and foremost, then you’ll mislead regarding the character of the agave, since the average consumer assumes that a mezcal made with wild agave is better than one made with cultivated agave, and thus pay significantly more for the former. A movement has emerged over the past decade or so, towards putting as much information as reasonably possible about the mezcal’s production, on the back label. However this is not to suggest that brands with sparse labelling information are less committed to transparency as a value. It might be more in the nature of what the brand owner wants to promote most about the product line, while still being 100% transparent about the product. Crushing the baked sweet agave espadín using a team of oxen. Epilogue It all comes down to the due diligence upon which the consumer is prepared to embark in order to investigate the extent to which his favorite mezcals are craft spirits. He should educate himself by asking the right questions of the brand reps, the bartenders and the mezcalería and restaurant staff. Test them all and try to discern their level of knowledge and forthrightness. And read the brand websites and blogs; what are they telling you, and what are they omitting and why. Try to have the unanswered questions answered by making inquiries. You might lose some respect for your favorite brands, and gain respect for others. Perhaps break down all of the foregoing into 10 – 15 determinants of craft-ness. Then grade the brands accordingly. I let the cat out of the bag at the outset when mentioning the word “continuum.” Brands lie along it. Those who have read my musings know that I tend to reject absolutes. Here, I have been clear that mezcal as a category should not be labelled as a craft spirit. In fact just because it’s labelled ancestral, should not be determinative that it’s a craft spirit; at least not until you’ve done that due diligence and investigated as many if not all of the determinants on your own list. And just because the distiller uses an autoclave should not cause you to discount the brand or factory. Briefly examining the brand Scorpion Mezcal using some of the determinants, exemplifies the kind of exercise we should be doing when placing any mezcal operation along the craft spirit continuum. In the Scorpion case, owner Douglas French works at the distillery daily, and is in charge of operations. His staff are mainly single mothers, some of whom have been with him for a quarter century. He welcomes visitors to his facility, with a bit of advance notice, and anything not noted on his labels he is happy to explain on a visit or a call or via email. Ask him the extent to which he has expanded his operation over the past two decades, and why. Labelling for brands such as his and others which date to the 1990s are usually as they appear, without a plethora of descriptors explaining means of production and tools of the trade, because that was the custom at the time, and the marketing has boded well for them. Why change what has worked in the past, and continues to do so? It is not necessarily indicative of a conscious attempt to inhibit transparency. Lest we forget flavor, and texture. It’s indeed curious that the umpteen defining characteristics of “craft,” many of which have been noted above do not mention quality of product, although a major related consideration, impact of the hand of the maker, is tangentially included in most cases. Three considerations are in order:

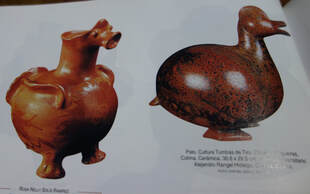

Enjoying a sip of artesanal mezcal from a tradtional half gourd or jícara. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com), a small, two-person federally licensed company with full transparency, and altruism as a primary focus of its raison d’être. Thus, it is a craft enterprise. Potters of San Marcos Tlapazola, Oaxaca, Retain Pre-Hispanic Tradition While Transitioning to Attract Mezcal AficionadosIn keeping with my efforts to support talented Oaxacan artisans, especially during these tough economic times of COVID-19, I wrote this article about the potters of San Marcos Tlapazola, known for its barro rojo or red clay pottery, and how one woman in particular has transitioned to taking advantage of the global mezcal boom by producing hand-turned items with agave imagery. Here's the article link, and a photo gallery of the range of red clay pottery: https://ezinearticles.com/?Red-Clay-Potter-of-San-Marcos-Tlapazola-Transitions-to-Mezcal,-Agave-Motifs&id=10299358 María making a series of copitas; no wheel, all formed by hand, with agave on one side and a face on the other. But she can also customize as requested. Finished red clay mezcal cups, initially designed by María's daughter Lucina when she was only eight years old. Every copita is unique. The family also makes complete dinnerware sets, as illustrated here at the 2018 village fair. Oven safe! Happy buyer scooped up this piece at the San Marcos Tlapazola Feria de Barro Rojo, 2018. María relaxes by doing oils, when there is time. Gloria is burnishing in the family workshop. Creations are burnished by hand, with no shellac, no varnish, no nothing except hand-labor, making every piece environmentally friendly and safe for using as drinking cups, cooking pots, etc. Simple, folky plates. The plan is to have the women make more elaborate ones, with agave, quiote flowering, and hummingbirds feeding. And plates with other scenes illustrative of different stages of the process of making mezcal. Other side has a raised face. Notice the form, finish, etc., all turned by hand, All in the family, photo taken at the 2016 San Marcos Tlapazola fair. Stands about 21 inches, campesino taking a break with bottle of mezcal. Both sides of this vessel are illustrated. Any shape, size, image is possible. Monkey planter stands about 22 inches. The classic chango mezcalero, the originals dating to the 1930s. Putting the finishing touches on a couple of pre-Hispanic Zapotec idols. All their pottery is fired in a rudimentary, open air above ground oven, fueled mainly with dried agave leaves (pencas) and flower stock (quiote). Rather unique tops, just for the asking. Thanks for viewing. Alvin Starkman: www.mezcaleducationaltours.com.

Preparing the oven for baking Agave karwinskii Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. About a decade ago, beginning in the wake of the 2008/9 US economic crisis, the pattern of migration between the United States and the state of Oaxaca got turned on its head. To a significant extent it was because of the initial stages of the global mezcal boom. With Lidia Hernández of Mezcal Desde la Eternidad Depending upon which statistic one reads, Oaxaca is either the poorest, or the second poorest state in all Mexico next to Chiapas. We have agriculture, and we have tourism. While export of mangos, black beans, tomatoes and all the rest have been a relative constant over the years, tourism has not; and the state has relied on beach going and culture seeking visitors for much of its economic fortune. Preparing the oven to bake Agave potatorum Tourists from diverse corners of the globe would flock to Oaxaca for its Pacific sun and sand, cuisine, craft villages, archaeological sites, colonial architecture and quaintness. But they would stop coming, especially from the US due to State Department warnings and journalistic sensationalism, at the drop of a dime: the (Mexican) swine flu epidemic, the 2006 Oaxacan civil unrest, drug cartel activity no matter where in the country, zika, and the list goes on. Prospective visitors would eventually forget and again select the state for vacationing … until the next scare; tourism’s economic impact was characterized by peaks and valleys. Mezcal is distilled in clay pots here in San Bernardo Mixtepec To address this schizophrenia, Oaxacans, both skilled and otherwise, would leave the state, emigrating in search of the American dream, or simply relocating to Mexico City or other large commercial centers where work was always available. The former is elusive, and it became especially so when a decade ago both Americans and migrants began either losing their jobs or some of their week’s hours. It grew to be much more difficult for Mexicans to get by, let alone remit money home to family in Oaxaca. Preparing a copper alembic for a first distillation in Zimatlán Enter the bold new era of mezcal. Over the past several years, both its production and the agave spirit’s popularity on the world state, have literally been increasing exponentially. Statistics bear this out. Agave americana Reverse migration has addressed the first prong of the phenomenon, in part due to the American economic crisis. That is, Oaxacans who were losing their jobs in the US began returning to their rural homesteads to help their relatives make mezcal. In earlier times they were leaving towns and villages and they headed north, in droves. Now, with no or less work than before, they were coming home, and for good reason given the spike in production and sales of the agave distillate. Checking oven depth, first hand I personally know of three cases in the hinterland of Oaxaca where immigration into the US has changed to emigration back to Oaxaca; in Santiago Matalán, in San Dionisio Ocotepec, and in San Pablo Güilá. In two cases the direct motivation was to help the family produce mezcal for both domestic consumption and export since these Oaxacans were in need of good reliable labor. In the third case it involved a construction worker who in his youth learned to make mezcal in Oaxaca. He then lived in California as a laborer for 20 years, and now had an opportunity to return home and build and work at his very own traditional distillery, and construct a home. Vintage cántaros are highly collectible, and hard to come by Oaxacans in the lower classes and rural areas have always imbibed the spirit. But a new phenomenon began around the beginning of this decade, with middle class urbanites all of a sudden jumping on the bandwagon. It was the early stages of the boom in the US which has given Mexicans a sense of pride in mezcal, as a quality sipping spirit much like a good bourbon or single malt scotch, rather than as a gut wrenching way to get drunk quickly. Remember those college years? Enjoying a meal with Doña Reina Sánchez, maestra palenquera and good friend Now, mezcal is respected globally, and there is increasing worldwide demand for it. So more mezcal is being distilled for both national and international markets. And, with this popularity has come an influx of visitors; to learn about it either to increase personal knowledge or with a view to opening a mezcalería in their home cities, to film and photograph it for business purposes, to sample and buy it out of pure passion for the spirit, and to begin their own brands for export. This client insisted that she help crush the sweet, baked espadín (Agave angustifolia Haw) These pilgrims, from as far away as Australia, are not as deterred as the normal tourist by what their governments and media warn. Mezcal tourism is a constant, and growing. New bride from San Marcos Tlapazola, learns the ropes to help her Santiago matatlán husband The actual production of mezcal is both causing the return of Oaxacans to their homeland as indicated, and keeping Oaxacans here. However there is more; while the motivation of many travelers for visiting Oaxaca is for mezcal (i.e. learning, documenting and of course buying), the spirit is actually having a much broader positive impact on the state. That is, when visitors come for mezcal, they also buy crafts, take cooking classes, dine in restaurants, stay in hotels, visit archaeological sites, and the list goes on, and on, and on. The dramatic impact is that emigration from the state is either halted, or at minimum significantly curtailed. And this keeps families together, in all walks of life. Hard at work with the quiote in San Dionisio Ocotepec Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). He has been witnessing the metamorphosis from the beginning. |

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed