|

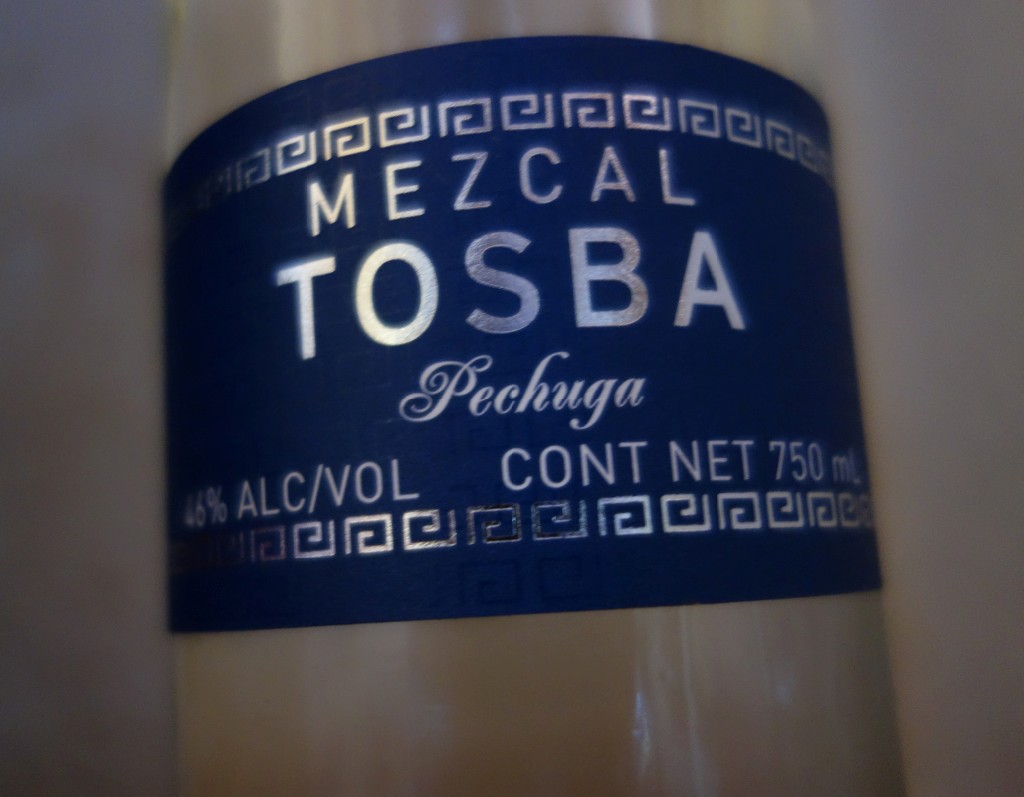

In January, 2014, NPR reported that people who follow mezcal and the growth of the market believed that the new kid on the block, Mezcal Tosba, “really could make it” (Planet Money, Episode 512: Can Mezcal Save A Village). By February, the 25 minute podcast had gone viral and become a hot topic of conversation (at least in Oaxaca, the state in south central Mexico where Tosba’s agave based liquor is produced) not only for the spirit’s aficionados, but also for many interested in microfinance, issues relating to migration, and the plight of rural Mexicans. Shortly after the airing of the program I had an opportunity to hear the story more directly, from the mezcal’s producers, at a presentation and tasting held at the In Situ mezcalería in downtown Oaxaca. I surmised that if indeed what I had gleaned was half accurate, I would eventually have an opportunity to learn for myself through visiting the palenque (a small artisanal distillery as it’s known in the state) and enjoying a sit-down with the maestro palenquero, Edgar González. Edgar and his cousin / business partner Elisandro González began with no background in agave production or mezcal distilling, and no money, yet were intent upon doing it all, by themselves, through learning; how to grow agave in their community, build a palenque, employ locals with likewise no experience in the trade, how to acquire the subtleties and secrets of making quality mezcal, and finally how to market their spirit in the US without agents or a distributors. The Mezcal Tosba partners are from the village of San Cristóbal Lachirioag, district of Villa Alta, where the palenque is located. Their non-agave / academic backgrounds and family dynamics, their motivation for getting into the mezcal business and their early guarded success are well chronicled in the NPR story. It was only after my November, 2014, visit to Lachirioag with Edgar and the cousins’ friend and promoter Oaxaca resident Darinel Silva, that I first listened to the actual NPR account. From the perspective of a mezcalophile and someone who regularly lauds the positive attributes of the state of Oaxaca, the González cousins’ Tosba saga offers much more, without detracting from that quality narrative. Darinel and I together with a Seattle based mezcal insider friend leave Oaxaca before 6 am. I had learned that the drive would take roughly five hours. Not wanting to spend the night in the village, we decided to prepare for a lot of driving and return to the city the same day. After climbing to over 9,000’ ASL and traveling through simply spectacular countryside with remarkably diverse vegetation (including the majestic Agave americana Oaxaquensis) and flecked with quaint colorful villages noted for predominantly agricultural production, we descend into Lachirioag – after only four hours. An unremarkable breakfast in a village comedor under our belts, we drive a further 20 minutes into a lush river valley where the palenque is located. En route we stop to gaze at Don Edgar’s plots of cultivated Agave angustifolia Haw (espadín), grown from seed. Over the past quarter century of drinking mezcal in Oaxaca, and more to the point visiting artisanal distilleries and speaking with the maestros producing the spirit, I’m almost always told by the palenquero that he learned to make mezcal from his father, his uncle, or his grandfather, with the tradition dating back as long as oral history would permit him to recall; usually four or five generations. Some have been taught well, and others produce a spirit of questionable quality, of course still good enough to keep the family revenue at an acceptable level above subsistence. So how is it that Don Edgar (let’s just say Edgar, since after all he’s only in his 30s), self-taught and without a family mezcal pedigree, is able to make mezcals that rival or better the quality of palenqueros producing for the likes of del Maguey, Pierde Almas, Koch, Vago, Alipus and the rest? Edgar began by experimenting, and claims he is still doing so; first by planting agave on the slopes of his own land, from seeds initially germinated just over a decade ago, and then finally beginning to distill over the last couple of years. We start with Tosba’s pechuga. My northwest coast agave aficionado exclaims that Edgar’s pechuga is the best he’s ever tasted, and I cannot disagree. I’ve been a fan of this mezcal incarnation for the past ten years or so. But what Edgar’s pechuga brings to the table is remarkable; a subtle medley of fruit flavors and a mere hint of sweetness, but most importantly it maintains or perhaps better yet enhances the agave notes. Even those who covet the spirit and are not fans of pechuga, would be hard-pressed to not request a second. All the fruit used has been grown on Edgar’s land. Since it is harvested throughout the year, some is initially frozen and brought out for distillation along with the seasonally fresh. “No, I don’t put the fruit in the copper pot with the mezcal. I hang it in the still above the liquid in this sack [showing us a polymer mesh bag, similar to those used to sell supermarket grapes and other fruit], together with the turkey breast. No one ever told me any different, and I didn’t know if there was a right or a wrong way to do it, so I just did it this way.” We explore the spacious palenque, and then the equally large interior rooms where we come across the stainless steel sterilizing and bottling machinery. To date Mezcal Tosba has exported to the US only four pallets totaling not more than 4,000 bottles. The equipment is certainly impressive, much more sophisticated than that of many operations which ship 20,000 bottles per year. “Yes, there has been the odd setback, but we’re now back on track,” he explains, then continues, “now let’s try some espadín, first something a little light, and then at 48% and at 50% because I want your opinion about which of the two higher ABVs you like best for when we start sending our mezcal north again, really soon.” “Please keep an eye on the ribs while we’re down at the falls,” he instructs his lone worker for this day, doubling as sous chef and tender of the two stills dripping mezcal. Three pieces of pork back ribs have been dangling on a wire about 15” above a brick base charcoal pit. They’d been marinated for a while and must now be slowly cured above the low flame for a couple of hours before grilling. With four shot glasses and a bottle of pechuga in hand, we walk down a long winding and rather steep overgrown dirt pathway, until reaching a flowing stream with crystal clear poolings. “All year round we catch white freshwater salmon, langostinos and a type of catfish, but we use netting rather than fishing rods,” Edgar boasts, then in answer to my question about fly fishing he elucidates, “let’s have a look at those deeper spots, since the current might be too strong for that kind of fishing.” We then head back up, but just a bit until reaching a steep spring fed falls. We sit on a series of large flat boulders while we drink and chat. To the continuous din of water descending over rocks we discuss Edgar’s longer term plan to eventually have some cabins to receive guests, and somewhat of a more formal open air kitchen area than currently exists. His buddy Darinel, my mezcal maven and I each pipe in with our opinions regarding how much more formal he might want to make this already exquisite natural environment. I’m already getting excited at the prospect of bringing groups of mezcal aficionados to learn more about mezcal and agave while participating in the process, and including nature walks, swimming, perhaps even hunting, and digging into Oaxacan regional cuisine. Talk turns back to spirits and agave. Edgar has a tract of land under cultivation with maguey approaching maturity. But this field of dreams is not just any plot of espadín. This one is completely encircled with coffee plants. The region is known more for coffee production than mezcal, despite the notoriety that the NPR episode has brought. He’s anxious to harvest, bake, ferment and distill the fruits of this particular crop more than others, and asks if I think the mezcal will taste different than other batches. I’ve been researching the impact on mezcal flavor of agave being in close proximity to different cash crops impacting terroir. I assure him that what comes out of that field will indeed have a special nuance. It must. We discuss environmental yeasts in this particular micro climate being impacted by the rich diversity of fruits harvested at different times of the year. No wonder his mezcals are so special, apart from Edgar’s dedication to the trade and penchant for learning through asking and experimenting. We’re tempted to jump into the base of the falls. “Wait until the warm season,” Edgar advises, “about from February through May, when the water will be much more agreeable in terms of temperature.” In any event, time is marching on, and I’ve resolved to not return after dark. Before returning to the palenque we head up to look at seedlings in two flower beds, and rows of five different varieties of maguey he is cultivating. Edgar is particularly proud of one series of rows of 2” – 3” tall agaves: “These over here, I don’t have a clue what you call this maguey. It’s native to this region and to my knowledge no one has even named it except by referring to it as silvestre [wild]. I once made a small batch of mezcal from it, liked it, so decided I’d like to make more. So I harvested some seeds, and now here we are. I have no idea how many years it will take until these plants reach maturity and are ripe for harvesting.” Back at the palenque the ribs are ready to be laid on the grill. Alongside, a thick iron comal sits on a stand made of rebar, just over over flames. Masa prepared by hand on a well-worked stone metate is pressed into tortillas then gingerly placed on the comal. En route to San Cristóbal Lachirioag Darinel had commented that only a couple of days earlier Edgar had distilled a batch of ensamble made from four agaves. Now, just before digging into the ribs, tortillas and salsa, seemed to be a good time to request a sample. “It’s not ready yet, too high in alcohol at 60%, so I have to reduce it, perhaps with colas from tobalá, so next visit,” Edgar advises. I implore him, however. “Why would you want to try something that I don’t like,” his curiosity then taking over. Finallly, over a comida described by my Seattle friend as the best meal he has experienced during his two week sojourn to Oaxaca, Edgar brings out the ensamble, 25% espadín and each of three wild agaves he elected to not name. Perhaps he thought that I would not be familiar with local parlance used to describe each.

We all agreed that the dominant note of the ensamble was sweetness, and none of us could pick up on a particular tone or flavor very well. Edgar was right, that with a little adjusting the mezcal would be much enhanced. Perhaps so, but I suggest that there is a reasonable probability that after resting in glass for six months, an exquisite medley of flavors and an agreeable nose might emerge. I manage to pry two liters from the reluctant maestro mezcalero. Thoroughly satiated in all respects, we drive back up to the village, Edgar accompanying us so we could meet his charming wife and two young children in their home. It’s already 4 pm, so arriving back in Oaxaca before dark is not in the cards. As dusk approaches on the return trip we hit the clouds, then light rain, all making negotiating the hairpin turns on the dirt roads somewhat of a challenge. I had completely forgotten that up in the mountains, at this time of year 6 pm spells darkness. Nevertheless, we return to the Oaxacan valley safely, recalling every detail of our visit to the Mezcal Tosba palenque, and the warmth and hospitality of Edgar, or on second thought despite his youth, yes, Don Edgar. Mezcal Tosba is a brand to be reckoned with. It will be around for a long, long time. After all, you can’t spend a decade putting your heart and soul into a project, not only for your own but also for the benefit of your fellow villagers without something great emerging. And let’s not forget the growing complement of mezcal aficionados relying on cousins Edgar and Alesandro González. Their continued success can only help mezcal’s reputation in the global spirits market to rise, even higher and faster. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca. He is the author of Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances.

1 Comment

|

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed