|

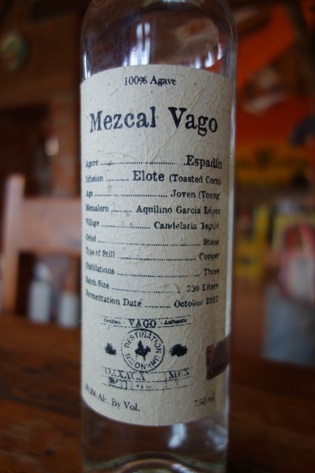

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. Mezcal Vago is one of a plethora of new brands of the agave-based spirit entering the US from the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca. Its sweet, swift success harkens back to the tenets of triumph in so many other entrepreneurial endeavors: hard work, vision and integrity. The owners of Mezcal Vago aren’t pioneers in the field of exporting artisanal mezcal like Mezcal del Maguey’s Ron Cooper. Nor are the two American partners directly steeped in generations of family tradition as was the late Don Pedro Mateo of the highly successful commercial brand Benevá. And to be sure, they don’t have the financial means of Armando Guillermo Prieto, who through an extensive promotional campaign is apparently en route to taking the mediocre (at best in the minds of some) Zignum “mezcal” through the profit stratosphere. Add to the Midas Touch of Mezcal Vago’s Judah Kuper and Dylan Sloan a combination of transparency in everything they do; more than fair compensation for their producers; passion for their product and what it represents; refusing to derogate from their vision; unconventional yet effective marketing; maintaining humility while at the same time being opinionated; taking a calculated gamble; and naturally a bit of good fortune with timely entry into the marketplace. The seed of Mezcal Vago has been well chronicled by Kuper and Sloan on their website. It’s a story of fortuitous circumstances, like that of so many innovators in a diversity of commercial enterprises. It’s been told time and again, though much less so in the world of mezcal if not other alcoholic beverages. _________________________________ Late one evening in early September, 2014, Kuper is holding court in his small, modestly outfitted office-cum-tasting-room, hosting a group of seven Colombian restauranteurs interested in importing mezcal for their eateries. He explains to them while they sip from a selection of a dozen or so Vago mezcals: “We’ve been in business for less than two years, and are already established in 17 states, with others ones as well as Canada and Europe on the horizon, so I have to be cautious about expansion because our growth must be maintained in check so that we keep to our vision. When I heard Colombia, it seemed like it might be just a small enough market for us, a good fit, so that’s why I agreed to come to the office tonight to meet with you.” Beginning about 2005, and continuing to date, the vision for many mezcal entrepreneurs throughout primarily the US and Europe, and also in Mexico City, has been to capitalize on the exponential growth in the spirit’s popularity across the globe, through pursuing a mainly profit motivated export business plan. As one such American commented in the course of seeking my tutelage about the spirit and its distillers back in 2007, “now is the time [for mezcal].” What she meant was the time to make money in the business of exporting mezcal from Mexico. Hence, she and her brash New York business partner descended upon Oaxaca. Kuper sees it this way: “There’s just so much smoke and mirrors in the [mezcal as well as other spirits] business, not from everyone who has jumped on the bandwagon, but from many, the ones who have little concern about what mezcal has represented to Mexicans over the centuries in terms of livelihood, culture and relationship with the environment. “In our case, we started with a grassroots campaign, enlisting the help of and targeting chefs, bartenders and spirits geeks, without paying them a cent, just serving them and finding out if we were on the right track with what we personally thought were amazing spirits made by sincere people with fascinating stories to tell. That’s how we started out. “Many other exporters have begun at the other end, with their marketers, their advertising and promotional firms; how do we promote this particular alcohol and distinguish it from tequila, what kind of a campaign should we mount, what’s trendy, sleek, contemporary and will sell – as opposed to what’s the best product we can get out there. Dylan and I each pooled a modest amount of money before making a commitment. We did our own website, took all the steps for export certification, and all the rest of the paperwork without lawyers or accountants. You know, we could have gone the way that others have gone, and in fact a Texas clearinghouse wanted to give us $100,000 as a kick-start. We rejected the offer, wisely as luck would have it, and went with someone who had the same vision as ours. With his much more modest financing, we looked after name and trademark, labels and business plan. We were off.” Kuper and Sloan are different from many [or dare I opine “most”] of the others, in ways aside from rejecting significant startup financing when offered. Kuper had been surfing up and down the Pacific coast of The Americas for eight years before grounding on a stretch of beach near the Oaxacan resort town of Puerto Escondido. He fell head over heels for a young Oaxacan nurse, whose father was a fourth generation palenquero (in Oaxaca, a small scale artisanal mezcal distiller). The lovebirds opened a palapa restaurant on the sand, and naturally included Kuper’s (soon-to-be) father-in-law’s mezcal. “I really liked Aquilino’s mezcals,” he explains “but had never given a thought to exporting it or getting into the business until I began to take notice that my restaurant customers really liked it and commented about the quality – the nose, the balance, the nuances, the approachability and everything else, despite it being upwards of 50% alcohol and sometimes more.” Kuper had previously been exposed to good artisanal mezcal, but its potential for leading to a livelihood for him, and turning the mezcal world towards him, remained in the recesses of his mind – until Aquilino came along. He comments to the Colombians that if it were not for all the laud that was being heaped upon his father-in-law’s mezcal, “I probably would have continued to be a surf bum, albeit eventually having to find some way to make a living to support my new wife and our baby.” Aquilino’s mezcals are produced in Candelaria Yegolé, a tiny hamlet of about 200 people, in the furthest reaches of the district of Tlacolula de Matamoros, bordering on the Sierra Sur region of the state. The area has a distinct microclimate with its particular environmental yeasts. Aquilino harvests his agave from steep mountain slopes with terroirs different from anywhere else. He uses a traditional copper pot still, or alambique. “Once Dylan and I decided to each pool our capital to test the waters,” Kuper continues, “we knew that we had to find a second producer, one whose product would both be entirely distinct from yet complement the mezcals that Aquilino had been producing.” Kuper and Sloan didn’t want to bottle and market a mezcal made by only one palenquero. “If you use only one distiller whose operation is in one microclimate, no matter how many different mezcals you’re producing, you’re doing yourself and spirits aficionados a disservice, because they will all by definition have a similar character,” Kuper suggests. “Selling the mezcal made by only one palenquero who ferments and distills in only one area of the state is limiting. We were looking for a completely different line of mezcals, produced by someone else in a different region using a different production method with a different family tradition. By chance we came across a cousin of my wife’s family, in a different district of the state, Sola de Vega.” They found Tío Rey, as he’s affectionately known, who for generations has been producing very different mezcals than those of Aquilino. Much of Tío Rey’s agave is grown in humid river valleys. Regardless of whether or not the same species or sub-species as Aquilino is used, the climate, terroir and environmental yeasts are so different that Tío Rey’s mezcals must inevitably be different from Aquilino’s. Combine that with the fact that Tío Rey employs clay pots rather than copper to distill, and the distinctions in the mezcal of the two producers becomes even more profound. And to top matters off, the palenqueros were each from a region more or less underrepresented in the export marketplace. “I respect so many artisanal palenqueros in the state, and in fact producers in other parts of Mexico. And of course also those exporters who have done what we’re still doing, that is seeking out the best product from the furthest reaches of the state. We’re still looking for at least one other producer to work with. We’ve driven hours and hours over umpteen back roads looking for a palenquero whose mezcal would nicely supplement what we already have in our stable and who would epitomize the cultural history of mezcal as we see it.”

Kuper acknowledges that Vago’s marketing plan has been to identify the four or five most respected artisanal bands of mezcal in the marketplace, and to improve upon what they’ve been producing. But at the same time he cautions: “I let Aquilino and Tío Rey do their thing, since their families have been making mezcal for generations. I’m just a student of the spirit, learning as I go along, always trying to produce a better product; and so we may have the odd discussion when I suggest something different or a little tweaking, but that’s about it. They’re the maestro palenqueros.” That humility and respect for those who know more, has been a hallmark of the success of Mezcal Vago. And it’s part and parcel of Kuper’s transparency in everything he does. He is outspoken about those producers and exporters who boast that they distill to proof and don’t add water – if indeed that’s the case. “So much depends on the water source, at what point you cut the tails (end of the distillation process), how you work with the tails if you’re going to use them, and so on,” he explains, then continues, that “dogmatism can inhibit your ability to produce a better mezcal.” Ask Kuper which of his palenqueros uses water to bring his mezcal to the preferred percentage alcohol, and how, and he’ll tell you. Ask him why his labels for his ensambles (blends) state the percentage used of each agave species or sub-species, and he’ll tell you: “I have nothing to hide. I know that there are producers out there who simply state the names of the agave used to produce an ensamble because they consider disclosing any more details tantamount to giving away a trade secret. But I would rather indicate percentages, so the consumer knows exactly what he’s getting, and is better able to refine his palate, distinguish nuances of particular agaves, and so on. If I simply stated on my label that the bottle contains espadín, tobalá and cuishe, how is that really helping the consumer, if for example espadín is 90% of the blend?” When asked about his labels, and their similarities in some respects to other brands on the market: “What I said before within the context of wanting to take the best and improve upon other artisanal mezcals in the marketplace, applies here as well. We have a massive respect for brands like Mezcaloteca which committed to sharing every detail of the process of creating its mezcals and out of total respect follow suit because that’s the way all labels should be. We felt that another brand that used a bit of agave fiber in its labels was an amazing idea and took it a leap further by making our labels 100% from the used agave mash after distillation. For many in the business, more taboo that the issue of water, is the use of chemicals to speed up the fermentation process, especially during the cold weather months. While neither he nor anyone else dare whistle blow, and although Kuper states that he will never work with a palenquero who adds anything to the fermentation vat, he understands that “other companies view chemicals as food for yeast” and that “they can improve fermentation rates and yields.” But he steadfastly asserts that “it’s not for us and never will be.” Enough said. With Sloan based in the US and Kuper in Oaxaca, Mezcal Vago is in an advantageous position in terms of being able to keep an eye on what their palenqueros are doing, and how. As Kuper puts it, “it’s important to have your foot in both worlds.” An industry insider from the US northwest sees it this way: “One partner is watching what’s going on with his production and the market from on the ground in Oaxaca, while the other is getting a balanced sense from living in the US. It’s really something; Vago is in every bar I visit.” Both Kuper and Sloan make a point of visiting each of their markets once or twice a year, travelling one out of every five or six weeks. And they are even more hands on. For example, Kuper picks up his federal “verificadores” (agents of the regulatory board, COMERCAM) to take them to his palenques to be sure that there are no delays in getting his mezcals certified for export; and he works with his wife, friends and neighbors doing all the bottling and labelling on their own. “This is a family business, and we want it to remain as such. After all, that’s the way it’s been for ages. You lose something if you deviate from the model which has brought you initial success. I know of export brands which have dramatically increased output but in the process have put a strain on production and their palenquero partners, through hiring lots of outsiders, building more and more stills, altering fermentation methods, and buying agave from further and further away from the villages where the mezcal is being produced. And you know what, I’ve witnessed those brands losing shelf space in the stores of major US retailers. Perhaps I’m naïve, but Dylan and I won’t let that happen to Mezcal Vago. It’s important to us that our palenqueros’ roots and age old means of production are respected.” Mezcal Vago will have its growing pains as have other producers and exporters, but the partners are steadfast in their resolve that their original vision must be maintained at all cost – even if it has to mean turning their backs on Colombia. “Mezcal is so pure, just agave, heat, water, and yeasts from the natural environment. It’s so simple. There is truth in mezcal. I want everyone who sips Mezcal Vago to be taken on a journey to real, rural Mexico, to get a sense of place with each sip. I even want them to sense something by merely picking up a bottle; I want them to feel like they’re holding something from an earlier era. Their hearts rates should race with a sense of adventure. I want them to appreciate the history of the families of our producers.” Kuper is referring to the pride in family tradition, which he believes must be maintained in order for their mezcals to retain the highest quality. Bringing in outsiders to help produce would change that. Introducing different production methods would change that. Using agave that has no relationship to the palenquero, his family or his land would change that. “We also feel the weight of our family’s needs on our shoulders, and respect that. Not a single drop of mezcal has ever been bottled until Aquilino and Tío Rey have been paid in full for their effort. We don’t subscribe to the philosophy of 50% when ordered and the other 50% when it’s on the pallet ready to leave the village for the border. Once they’ve distilled, they have complied with their primary obligation to us, that is, to produce a quality spirit. They should not have to wait any longer to get paid. If our mezcals are a bit more expensive that some others, and certainly that’s the case, it’s because we pay our palenqueros sometimes even more than they want. If there’s any price negotiation, it’s us trying to pay more to them, really. I don’t like labels, but I suppose it’s akin to a fair trade practice to the extreme. Aquilino and Tio Rey are the keys to our success more than any other factor and so we must treat them as such. But it shows in the quality they keep on producing for us.” Previously, Aquilino didn’t much ponder the relationship of his family with the land, water, agave, and ultimately his mezcal. He was too busy eking out a subsistence though sufficient living. Both he and Tío Rey in fact exemplify mezcal as permaculture. They used to take it all for granted. But now, with mezcal lovers from all corner of the globe making pilgrimage by descending upon Oaxaca, and asking to visit Candelaria Yegolé and the hinterland of Sola de Vega, to meet and pay homage to the producers of Mezcal Vago, Aquilino and Tío Rey now get it, and they feel an enhanced sense of pride in their craft; which in turn feeds the desire to keep producing mezcals of excellence, as tribute to their heritage. The Colombians left Oaxaca, sold on Mezcal Vago after learning of the existence of the brand only a couple of hours earlier. Whether they can convince Kuper and Sloan that their market is worthy of the mezcals of Aquilino and Tío Rey, is a question yet to be answered. Alvin Starkman owns and operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca. He is the author of Mezcal in the Global Spirits Market: Unrivalled Complexity, Innumerable Nuances, (Oaxaca, MX: Carteles Editores – P.G.O., 2014)

0 Comments

|

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed