|

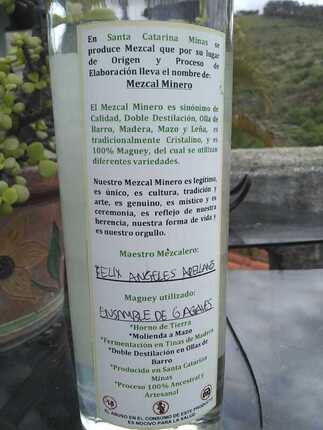

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. Within the first couple of hours of leading a Oaxacan mezcal educational tour, two of the most commonly asked questions are, “what’s the difference between a mezcal ensamble, a mezcla and a blend,” and, “why do the palenqueros do mixes in the first place.” In this article I do my best to answer both questions, based on having been around agave distillates primarily in the state of Oaxaca for the past 30 years, and on a very frequent basis over the past couple of decades having spoken with tens of traditional distillers and their family members (who produce mezcal ancestral or artesanal) regarding such queries. Mezcal: An Ensamble, a Mezcla, or a Blend Many mezcal aficionados nonchalantly toss about the word “blend,” such as stating “oh, so it’s a blend of tobalá, madrecuixe and espadín.” There is certainly debate and disagreement amongst both the mezcal geeks/experts and the distillers (even from the same village) regarding nomenclature when it comes to mixing different species and sub-species to arrive at a desired end product. But there is, or at least in my opinion should be, a consensus distinguishing a blend on the one hand, from a mezcla/ensamble on the other. Blends are commonplace in the world of mezcal, but typically not in the world of artesanal or ancestral production. Think of a blended whisky. Take two or more finished products, blend them together, and you get, for example, Johnny Walker Red Label, a blended whisky (as opposed to a single malt). Now switch to agave distillates produced in the large modern factories in Oaxaca such as those en route to San Pablo Villa de Mitla or on the outskirts of Santiago Matatlán, just to name a couple of locales. These factories can and do buy large quantities of distillates from various sources, bring them to a central facility, blend them, and voilá we have blended mezcals. Or they can produce different batches at the same distillery, and then blend them together. The foregoing is an easy way to distinguish a blended mezcal from the others, regardless of whether we term them ensambles or mezclas. Now think of the mezcals commercially available through retailers in the US, Canada, the UK, and elsewhere around the globe. The labels typically include the word “ensamble” to identify a mezcal made from two or more distinct varietals of agave. Usually the piñas have been baked together, then crushed together and placed in a fermentation vessel, and finally the mosto as it’s known, is distilled. Thus, the mixing starts at the beginning rather than at the end. A variation on the theme is baking in different lots and/or the agave at different times, but then crushing and the rest, together. But some palenqueros state that the broad means of production should properly be termed a mezcla rather than an ensamble. And so the disagreement remains, and will likely continue into the relatively distant future. A few of my palenquero friends steadfastly maintain that it’s a mezcla when the mixing starts at the beginning, and an ensamble is what we (should) refer to as a blend. But what happens when those same palenqueros’ distillates are bottled, labelled and shipped abroad? The label pretty much invariably states “ensamble.” Why, one might ask, is there is such groundswell of disagreement between the two camps? Many of those imbibers in the English (and I suppose French) speaking world know the word “ensamble” but not the Spanish word “mezcla.” The word “blend” would never be used since to many it has a less than quality-product connotation. And so on the store shelf we find mezcal ensambles, and typically not mezclas. In my opinion we can use the words mezcla and ensamble interchangeably, just as tow-MAY-tow and tow-MAH-tow. Don’t get hung up on something akin to that which etymologists often disagree concerning. But do recognize the difference between blends on the one hand, and mezclas/ensambles on the other. Top Five Reasons Palenqueros Mix Different Varietals of Agave !. Several years ago a client asked one of my palenquera friends how she determined how much of each species she mixed together to arrive at her ensamble of six agaves. Her answer was rather simple, easy to understand and made an abundance of sense: “we brought one donkey-load of each type of agave to the palenque, and that’s how we decided.” Before the modern era of mezcal, which dates to no earlier than the mid-1990s more or less, foraging was the order of the day, and often regardless of what kind of agave was put in the oven and further processed, the end product was called just plain mezcal: not madrecuixe, nor tobalá; termed neither an ensamble or a mezcla. That’s what mezcal used to be. I recently purchased 10 liters from a neighbor who hails from a far-off village, some six hours away from the city of Oaxaca. Here in the state capital, specifically in our neighborhood, he flogs his villagers’ honey, coffee, and mezcal distilled in clay. He described the mezcal as made from maguey campestre, that is, agave from the countryside. It was just plain mezcal, produced as has been the case dating back hundreds if not thousands of years. There are still palenqueros who harvest whatever they can, from wherever they can, in as large quantities as time, distance and beast of burden allow. But these palenqueros are in the minority, rarely encountered by our readers, except those who want true far-off adventures to where one never knows what will be sourced; with what species of agave the purchase has been comprised. 2. The polar opposite of 1. above, is when a palenquero combines different types of agave because the ultimate taste is extremely agreeable to him. The corollary also sometimes comes into play. That is, he will refrain from mixing certain varietals together because the combination does not yield a good flavor. Typically, nose and finish do not enter the equation; taste rules. 3. The objective of many palenqeros is to completely fill as many fermentation vats as are to be used for the particular oven-load of baked, sweet, crushed agave. Often roughly a ton of the mash fills a wooden slat vat. While all is based on science, it is an art, a skill, which doesn’t always work out as planned. Sometimes, for example, eight tons of agave, one ton of each varietal, are baked together, then segregated with a plan to ferment one ton of each in a particular vat. But occasionally there is a bit left over from a couple of the species; the extra won’t fit into the vats for which each sub-species has been earmarked; That is, without seriously overflowing once water has been added and fermention begins in earnest. And so the palenquero will combine the excess kilos together into a vat, resulting in a particular mezcla which may never be repeated; unless of course it yields a particularly agreeable ensamble. 4. Sometimes a palenquero will combine two species of agave, in circumstances wherein one has a low sugar content, and the other much higher. The motivation is that this may result in a higher yield of the ultimate mezcal. 5. Finally, at least one palenquera friend is rather sensitive to what she is compelled to charge for mezcal produced from a particular varietal of agave, based on typical yield. She has explained to me that a mezcla sometimes is produced in a way that reduces the ultimate cost she must charge, yet retains much of the flavor of the more expensive (low carbohydrate content) type of agave. She used the example of combining tepeztate with some espadín in such a way that the end product still has a classic tepeztate taste, yet is not as expensive as it would have to be if she were to distill 100% tepeztate. So there you have it, my take on nomenclature, and what I have gleaned to date as to some of the reasons ensambles of mezcal and agave distillates are produced in the state of Oaxaca.

Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com).

0 Comments

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. How can we determine if our preferred brand of mescal is properly termed a craft spirit? In this opinion piece I attempt to refrain from using brand names of mezcals and agave distillates we tend to consider being traditionally produced (i.e. ancestral or artesanal). The reader, after reviewing the following, will likely be able to place particular mezcals along a craft spirit continuum. And so right off the bat my thinking about the topic should be clear, that is at least my singular broad conclusion. Arguably the most primitive of agave distillate operations this century. Understanding and defining craft spirits is a complex topic with several nuances and points of view, even for those in the know. Adding mezcal to the mix further complicates, and makes arriving at concrete answers even more dumbfounding. Craft Spirit Definitions A search for a clear definition of “craft” within the context of spirits yields many results. Typically it denotes drink made in a traditional or non-mechanized way by an individual or a small company, or made using traditional methods by small companies or companies and people that fashion it. This alone reveals problems which arise within the mezcal context, when one tries to define “traditional,” “non-mechanized” and “small.” When the word “craft” is used as a verb, we fine definitions such as “to make with care or ingenuity,” and “to exercise skill in making, typically by hand.” Again there are issues when parsing the phrases to determine their applicability and relevance to mezcal. The community of the American Crafts Spirits Association (ACSA) has different definitions of “craft,” and thus has elected to not live by a singular definition, but rather to allow its members to each come up with an interpretation which serves his/her needs. However it has indeed passed judgment on what it considers to be subsumed by the term “craft spirits,” and what it considers to be a “craft distillery.” And so ACSA believes that: Craft Spirits means (1) a product made by a distillery which values the importance of transparency in distilling, and remains forthcoming regarding the spirit’s ingredients, distilling location, and aging and bottling process, (2) a distilled spirit produced by a distillery producing fewer than 750,000 gallons annually, and (3) no more than 50% of the Distilled Spirits Plant (DSP) is owned directly or indirectly by a producer of distilled spirits whose combined annual production of distilled spirits from all sources exceeds 750,000 proof gallons removed from bond. A craft distillery is a facility which values the importance of transparency in distilling and remains forthcoming regarding its use of ingredients, its distilling location and process, and aging process. It produces less than 750,000 gallons annually. It directly or indirectly holds an ownership interest of 50% ownership or more of the DSP. The American Distilling Institute (ADI) is another industry organization. It provides a craft spirit certification designation. For ADI to certify:

The most sophisticated of mezcal distilleries, the polar opposite of craft. Factors to Consider Based on the foregoing, as well as from a review of several articles centering upon applicable definitions, it is fairly easy to conclude that within the mezcal context a simple answer should not reasonably be proffered, because of the lack of uniformity in the agave distillate industry; perhaps arguably distinct from, for example, the single malt scotch pursuit. However we can examine a number of factors and reach our own conclusions, both regarding our favorite brands of mezcal, and the spirit in general:

Emptying a copper mezcal alembic in San Lorenzo Albarradas, Oaxaca Discussion Within the Mezcal Context Ownership of Brand / Distillery: Should percentage or type of ownership of the distillery be a factor in designating a mezcal brand as a craft spirit? Perhaps instead we should examine control of means of production. We know that Diageo, Pernod Ricard, Samson & Surrey and Bacardi are all in the mezcal business. If the distillery proper is still owned by the family of palenqueros, but decisions are made by the conglomerate, how does that change our thinking? How “hands-on” can the family be, other than participating in all processes, if its members are excluded from the decision-making process? Ownership of a brand by a multi-national corporation should not be the determining factor. In many cases sale to one of the big boys simply enables the brand to achieve global exposure than it otherwise would not have enjoyed, a good thing in terms of helping the family of palenqueros, the community, promotion for the region, etc. But once the non-Mexican corporate entity begins to tamper with means of production and tools of the trade, then the other factors come into play. If the corporation, let’s say Pernod Ricard, has purchased 100% of the brand from the previous owner(s), but leaves day-to-day management to them, can the brand still maintain a craft spirit status? Samson & Surrey actually boasts its “craft spirits portfolio” and advantageousness of having the “resources of a larger company.” It appears to be doing all the right things. Its reference to “human touch” would bring its products into the fold of “craft,” noted above as in “with care.” Let’s examine Mezcal Benevá, a brand which most would likely agree does not produce a craft spirit, even though over the past couple of years it has added equipment to bring some of its production under the rubric of the term artesanal. The brand is 100% privately owned by a Oaxacan family (the last time I spoke with ownership), some of the members of which have a strong pedigree of production dating back generations. Its annual production is less than 750,000 gallons, but sales are more than 100,000 gallons. It lacks transparency only to the extent that, to my knowledge it does not offer access to its plant by the general public; otherwise in my opinion it is transparent in all determinative respects. The main issue with Benevá is means of production and tools of the trade, employing computer technology and finely calibrated scientific equipment, with its autoclaves, stainless steel equipment, diesel fuel and the rest. How different is Benevá from Lagavulin single malt scotch, owned by Diageo? Would you consider Lagavulin a craft spirit? Diageo is a publically traded company. This brings us to “values.” Is the first priority of a company which trades on the stock market to answer to its shareholders (i.e. improve bottom line above all else; of course I’m not referring to “green” companies)? If so, then where do its values lie? Do we put Diageo in the same category as Benevá, both as non-craft enterprises? Lagavulin appears to maintain tradition, but produces well over 100,000 gallons annually, and I would suggest at the end of the day must answer to its parent company. Equipment Employed / Production Methods: If a mezcal brand has several distilleries producing for it, using traditional, non-mechanized production methods and tools, but produces one million gallons annually, is it still producing a craft spirit? If one of the brand’s products is a “blend” in the whisky sense, that is, not a traditionally made mezcal, should we refrain from terming the blend a craft spirit? What if a palenquero elects to use a gas powered crushing machine rather than mashing by hand or with horse and tahona, just to make like a bit easier for him? Is it no longer “craft” because the product arguably does not fit within the definition of “traditional” or “non-mechanized?” What if the palenquero switches to an autoclave for one or more reasons, including wanting to:

Volume Produced: I have already touched upon the volume of production index. I don’t think that volume should be a factor, at all, if it is clear from an examination of all the other determinants whether the brand or the distillery is craft, or not. If we cannot pigeonhole by looking at the rest, then, and only then, perhaps an examination of volume produced can correctly sway us in one direction or the other. Or, using the continuum model, take us closer to one end versus the other. Staff Numbers and Relationship to Owner(s): This, once again, should be one of the lesser important factors in making the craft spirit determination. Staff numbers reflects success of the brand and little if anything more, which returns us to numbers (i.e. gallons produced). What is the maximum staff numbers allowed for the brand, or distillery production team, to be considered craft? Returning to Benevá, the Zignum brand is just down the road, but owned, to my recollection, by non-Oaxacans or at minimum non individuals whose families emanate from nearby mezcal producing villages. Yes the two are large sophisticated operations, and likely each has a comparable number of employees. But in the case of Benevá, likely most are family simply because in a general rural Oaxacan sense, owners tend to prefer hiring family whenever practicable. The Zignum ownership likely hires workers who are not family because ownership is comprised of “outsiders.” So as relative to Zignum, Benevá can boast at least one half of this craft dimension, that is, the strength of family relationships from top to bottom. But certainly this does not mean that Benevá is a craft spirit. After the mezcal bake; tasting a piece of baked agave to ensure sweetness is okay. Transparency and Values: Should the consumer always be able to readily learn the name of the distiller and location of the distillery? There are typically reasons for withholding this information. The reader can judge for herself the validity, and the extent to which this should impact her thoughts about whether or not the mezcal should still be considered craft. Reasons include:

Where I think a mezcal’s characterization should be impacted, is regarding misrepresentation of the contents of the bottle. And regretfully this does occur. There are brands of traditionally-made mezcal which label every bottle, except those distilled with espadín, as being made with wild agave; wild tobalá, wild madrecuixe, wild mexicano, and all the rest. Now yes of course there are still wild agaves up in the hills and otherwise far off, but currently virtually every agave currently used to produce mezcal in the state of Oaxaca is under cultivation. How could the Diageos and the Pernod Ricards of the world, each with a global reach, meet demand if they were not having these species cultivated for them. A good friend of mine has 16 different varietals under cultivation, only one being espadín. Yes there is literature stating that only after the fifth generation of production, should one begin to classify the plant as cultivated. But how does the public know? The better and more honest route is to label “semi-wild” or “semi-cultivated,” or not preface the name of the species with anything. Not following this suggestion illustrates a significant lack of transparency. But thankfully the good and the righteous outweigh the bad and the scoundrels. It all comes down to the values the brand and the palenque embrace. If profit is first and foremost, then you’ll mislead regarding the character of the agave, since the average consumer assumes that a mezcal made with wild agave is better than one made with cultivated agave, and thus pay significantly more for the former. A movement has emerged over the past decade or so, towards putting as much information as reasonably possible about the mezcal’s production, on the back label. However this is not to suggest that brands with sparse labelling information are less committed to transparency as a value. It might be more in the nature of what the brand owner wants to promote most about the product line, while still being 100% transparent about the product. Crushing the baked sweet agave espadín using a team of oxen. Epilogue It all comes down to the due diligence upon which the consumer is prepared to embark in order to investigate the extent to which his favorite mezcals are craft spirits. He should educate himself by asking the right questions of the brand reps, the bartenders and the mezcalería and restaurant staff. Test them all and try to discern their level of knowledge and forthrightness. And read the brand websites and blogs; what are they telling you, and what are they omitting and why. Try to have the unanswered questions answered by making inquiries. You might lose some respect for your favorite brands, and gain respect for others. Perhaps break down all of the foregoing into 10 – 15 determinants of craft-ness. Then grade the brands accordingly. I let the cat out of the bag at the outset when mentioning the word “continuum.” Brands lie along it. Those who have read my musings know that I tend to reject absolutes. Here, I have been clear that mezcal as a category should not be labelled as a craft spirit. In fact just because it’s labelled ancestral, should not be determinative that it’s a craft spirit; at least not until you’ve done that due diligence and investigated as many if not all of the determinants on your own list. And just because the distiller uses an autoclave should not cause you to discount the brand or factory. Briefly examining the brand Scorpion Mezcal using some of the determinants, exemplifies the kind of exercise we should be doing when placing any mezcal operation along the craft spirit continuum. In the Scorpion case, owner Douglas French works at the distillery daily, and is in charge of operations. His staff are mainly single mothers, some of whom have been with him for a quarter century. He welcomes visitors to his facility, with a bit of advance notice, and anything not noted on his labels he is happy to explain on a visit or a call or via email. Ask him the extent to which he has expanded his operation over the past two decades, and why. Labelling for brands such as his and others which date to the 1990s are usually as they appear, without a plethora of descriptors explaining means of production and tools of the trade, because that was the custom at the time, and the marketing has boded well for them. Why change what has worked in the past, and continues to do so? It is not necessarily indicative of a conscious attempt to inhibit transparency. Lest we forget flavor, and texture. It’s indeed curious that the umpteen defining characteristics of “craft,” many of which have been noted above do not mention quality of product, although a major related consideration, impact of the hand of the maker, is tangentially included in most cases. Three considerations are in order:

Enjoying a sip of artesanal mezcal from a tradtional half gourd or jícara. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com), a small, two-person federally licensed company with full transparency, and altruism as a primary focus of its raison d’être. Thus, it is a craft enterprise. |

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed