|

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

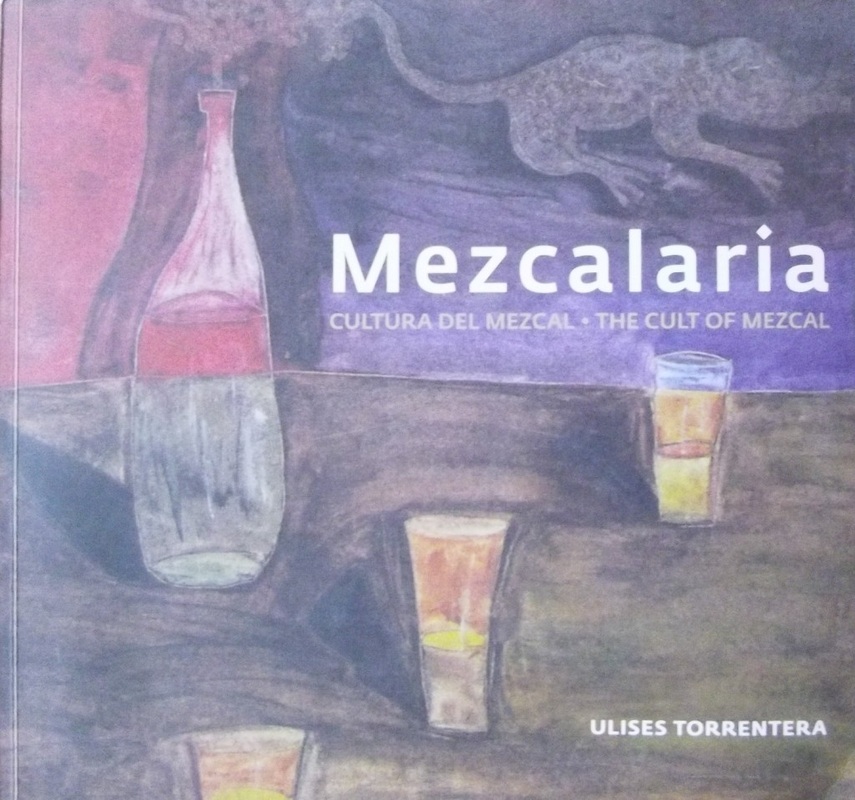

Mezcalaria, Cultura del Mezcal, The Cult of Mezcal (Farolito ediciones, 2012) is the third edition, first bilingual (English-Spanish), of the seminal 2000 publication by author Ulises Torrentera. The book is highly opinionated on the one hand, yet on the other contains a wealth of both historical and contemporary facts about agave, mezcal and pulque. Torrentera places his subject matter within appropriate social, cultural, ethnobotanical and etymological context, at times referencing other Mexican as well as Old World spirits and fermented drinks. And where fact is uncertain, or when Torrentera feels the need to supplement in order to hold the reader’s interest, he infuses with myth and legend. Torrentera takes the reader far beyond the decades old introductory book, de Barrios’ A Guide to Tequila, Mezcal and Pulque and much deeper into the field of inquiry than the more recent series of bilingual essays in Mezcal, Arte Traditional, although the latter does include excellent color plates (the Spanish first edition of Mezcalaria contains a few color plates). It stands at the other end of the spectrum from the monolingual coffee table book Mezcal, Nuestra Esencia and is far more comprehensive than the English portion of Oaxaca, Tierra de Maguey y Mezcal. Torrentera’s passion for mezcal rings loud and clear. In discussions with him and in the course of hearing him hold court, he has repeatedly indicated that it’s crucial that more aficionados of alcoholic beverages taste and appreciate all that mezcal has to offer. That’s his motivation for writing, speaking, and exposing the public to mezcal in his Oaxaca mezcaleria, In Situ. The spirit, paraphrasing his viewpoint, leaves its main rival tequila behind in its wake, primarily because of the numerous varieties of agave which can be transformed into mezcal, the broad range of growing regions and corresponding micro-climates, and the diversity of production methods currently employed, the totality yielding a plethora of flavor nuances which tequila cannot match. His treatise, on the other hand, to some extent does his raison d´être a disservice. He is overly critical of mezcal that is not to his liking. For example, in the Prologue to this first English edition (don’t let the poor and at time incomprehensible translation of the Prologue dissuade an otherwise prospective purchaser; the balance of the book is well translated) Torrentera writes of mezcal with more than or less than 45 – 50% alcohol by volume: “above that graduation [sic] the flavors of mezcal are lost and there is more intoxication; if it is below this one cannot appreciate the organoleptic qualities of the beverage.” He also writes that unaged or blanco is the best way to appreciate mezcal. He continues that in his estimation “cocktails are the fanciest manner to degrade mezcal.” Indeed, I regularly drink one particular mezcal at 63%, which is exquisite, and numerous other mezcales in the 52% - 55% range which my drinking partners and I enjoy; we appreciate flavor nuances without becoming overly intoxicated. At the other end of the spectrum, a recent entry into the commercial mezcal market, produced in Matatlán, Oaxaca, is 37%. The owners of the brand held well over 50 blind taste testings in Mexico City, including mezcales of less percentage alcohol, of greater potency, and of popular high end designer labels; 37% won out by a wide margin. In the first year of production it shipped 16,000 bottles of 37% alcohol by volume to the domestic market only; not bad for a mezcal lacking organoleptic qualities. Regarding the blanco/reposado/añejo issue, why not encourage novices to try it all and decide for themselves? Why dissuade drinkers of Lagavulin, or better yet Glenmorange sherry or burgundy cask scotch from experimenting with mezcal aged in barrels from French wine or Kentucky bourbon? While I appreciate Torrentera’s zeal and his belief, his dogmatism may very well serve to restrict sales of mezcal and inhibit valiant efforts to find convertees. Many spirits aficionados might prefer a mezcal which he does not recommend. Furthermore, if mixologists and creative bartenders can increase sales and market mezcal through mixing mezcal cocktails, isn’t that what the Maestro wants? Torrentera’s reflections are otherwise sound and should find broad agreement with readers, be they mezcal or tequila aficionados or novices, or those who are otherwise followers of the industry. I’ve often expressed his point that far too many exporters and large scale producers are padding their bank accounts at the expense of campesino growers and owners of small distilleries, the mom and pop “palenques” as they’re termed in the state of Oaxaca. He laments the regulatory direction mezcal appears to be heading, and pleads for change in the NOM (Norma Oficial Mexicana) and for a better and more discerning and detailed system of classification. He warns of mezcal heading in the direction of tequila in terms of homogenization. Torrentera’s work is the most comprehensive and detailed endeavor available in English, which combines and synthesizes literature about agave (historical uses and cultural importance), pulque (within global context of fermented beverages) and mezcal (as one of a number of early distilled drinks). He appropriately criticizes, mainly in the Prologue, academic studies which have provisionally concluded, using a bastardized form of scientific method, the existence of distillation in pre-Hispanic times. The author shines in his compiling, extensively drawing from, and quoting diverse bodies of work; scholarly, historical anecdotal, as well as both secular and religious Conquest era laws and decrees. His bibliography is impressive. He correctly cites inconsistencies in and difficulties interpreting some of the centuries old references, allowing the reader to reach his own conclusions. If a criticism must be proffered, occasionally it is difficult to discern when he is quoting versus using his own words. But this is likely an issue with editing and printing than fault of Torrentera. At times he does neglect to indicate dates and sources, making it hard to determine precisely how much is independent research. Footnotes would have helped in this regard, and also would have made it easier for the reader to go to the original source material. Torrentera vacillates between seemingly attempting to write in an academic manner, and inserting intra-chapter headings and content which would appear to be attempts at humor. To his credit, however, the difference is easily discernible, and accordingly the reader should have no difficulty distinguishing fact from lightheartedness. Mezcalaria, Cultura del Mezcal, The Cult of Mezcal, is an important and extremely comprehensive body of work. It should be read by everyone with an interest in agave, mezcal (or tequila) and / or pulque. Torrentera is to be congratulated for compiling what no other writer to date has been able to do. Alvin Starkman has been an aficionado of mezcal and pulque for 20 years. A resident of Oaxaca, Alvin frequently takes visitors to the state into the outlying regions of the central valleys to teach them about mezcal, including different production methods, flavor nuances and the use of diverse agaves. Alvin has written extensively about mezcal and pulque and has recently begun compiling a body of literature: http://www.oaxaca-mezcal.com. He can be reached at [email protected].

1 Comment

|

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed