|

The direct and easily discernible effect of the surge in mezcal tourism for the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca, is the dramatic spike in sales of the agave spirit. Production has increased approximately fourfold between 2010 and 2017, and that’s not even including uncertified mezcal (which has not passed through the auspices of the federal certification/regulatory board). Consider the positive impact on the lodging industry, and on both Oaxaca city restaurants and rural eateries where production occurs. Mezcal tourism impacts the economy in these and a plethora of other ways, even during times of the year when visitor numbers to the state are traditionally low. But this is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. On a recent warm, sunny afternoon, for the first time that I can recall, there was a lineup leading outside the front door at CATOSA bottle distributor in the city suburb of Los Volcanes. Everyone was waiting to place orders for bottles destined to be filled with the iconic Mexican spirit. The numbers of both company office staff and warehouse personnel had indeed been increasing over the past couple of years. But now, even with a good complement, the distributor could not keep up. Part of the problem was that because of a dramatic increase in sales, CATOSA was short of inventory from one particular bottle factory outside of the state, and so customers had to ponder, at least temporarily, what size and shape to buy. And then there was the issue of which top to use for the bottles currently available, at least on a provisional basis; natural or artificial cork, wood, plastic, metal, color, and; whether or not plastic sleeves to shrink wrap the stopper should be used, required or not. These were not even the large commercial clients who would regularly order significant quantities for domestic and export mezcal sales. They were small scale distillers with equally modest retail outlets alongside their palenques; owners of city mezcalerías, bars and restaurants which would buy bulk mezcal and then retail by the shot or in 750 ml glass bottles; as well as individuals planning to gift the spirit with a personalized one-time label as a token memory of a family rite of passage celebration (wedding, quince años, baptism, etc.). Related to the increase in bottle sales are the paper and printing industries, and the graphic design and related art vocations, each business competing for new opportunities to work with entrepreneurs both developing brand recognition and expanding market reach. The handmade paper factories a short distance outside the city of Oaxaca as well as downtown and suburban printers, have all noted a sharp increase in client numbers and in sales for existing mezcal enterprises. But there is more. Oaxaca has traditionally been a veritable wasteland for those interested in acquiring antiques and collectibles. But now there is value perceived in anything even remotely related to agave, mezcal and pulque: old wooden mallets (mazos) used for crushing baked agave in preparation for fermenting; cracked clay distillation pots (ollas de barro) which can still be used as planters; the shell of the fully tapped majestic Agave americana or salmiana which is also used as an adorning planter; ancient rusted laminated metal condensers, an integral part of ancestral distillation; vintage postcards portraying distillation or harvesting aguamiel which when exposed to environmental bacterial becomes pulque; iron implements used in cutting agave from the field such koas; metal tools used to scrape the inside of agaves so as to induce the seepage of aguamiel into the well (raspadores), and; vintage clay pots (cántaros), used in decades past for storing and transporting mezcal. There is of course the most highly collectible of them all, the clay vessel in the shape of a monkey, chango mezcalero, dating to the 1930s and used to market and boost mezcal sales. While it is a stretch to suggest that collectors now visit Oaxaca for the principal purpose of acquiring antiques, those whose interest have been piqued by agave and its cultural importance over millennia, now find a new reason to spend more time, and money, in the state. It’s not only the collectors of vintage who are making a pilgrimage to Oaxaca in search of anything old and related to agave. Entrepreneurs are finding ways to benefit by selling online. Their clients are both collectors, and owners of American bars, mezcalerías and Mexican restaurants with a healthy complement of mezcal. Often the latter visit Oaxaca to both learn about mezcal, and to return to their home cities with paraphernalia to adorn their establishments. Their numbers include American bars and restaurants in Seattle, Portland, Carmel, Dallas, Houston, Austin, Baltimore, D.C., Chicago and New York, with cities in Canada slow on the update yet gradually catching on. They also converge on Oaxaca from a broad range of cities throughout Mexico. Success has come relatively effortless for such retailers. Almost to a number, at least in the case of American establishments, their owners in due course make return visits to Oaxaca, now with their staff. Selling mezcal is much easier if your employees have been here and learned first-hand about artisanal production. There is a newfound passion, unattainable through merely reading articles and books or watching YouTube videos. And so the numbers visiting Oaxaca are literally increasing exponentially. Some mezcal brands are offering incentives to bars by giving comps: “if you buy 25 cases of our mezcal, we’ll provide a free trip to Oaxaca for two of your premier bartenders.” And it works. Antique and vintage items are not the only class of collectible being retailed in Oaxaca and earmarked for mezcal aficionados. Not since the tourism boom which began in the 1960s with hippies converging upon Oaxaca in search of the magic mushroom, have craftspeople begun to think outside-of-the-box. Thanks to mezcal we now have more than the typical blouses hand-embroidered with flowers, wool rugs woven with motifs representative of the Mitla archaeological site, carved wooden figures (alebrijes) with dragons, and traditional designs on clay pots and figurines in terra cotta, barro negro and green glaze. Just walk into higher end downtown Oaxaca retail outlets like La Mano Mágica, or saunter through any of the umpteen craft shops and indoor marketplaces. Agave and mezcal are now well-represented, whereas only a decade ago it was “same old same old.” Craftspeople and their retailers are now in a position to double and even triple sales by marketing anything related to mezcal and agave. We can easily find contemporary changos; drinking vessels for spirits in hand-blown glass or in clay fashioned with raised agave leaves; ceramic water and pulque serving pitchers again with agave; hand woven agave table runners, coasters and bottle carriers; carved wooden boxes, bar stools, sofas and more, all with the succulent whittled into the wood; jimador stone carvings; linen shirts with embroidered agave; silver agave earrings; etc., etc. etc. Whether a novice with merely a passing interest, or an ardent mezcal aficionado, it’s almost impossible to resist buying just something, anything relating to mezcal, pulque or agave, regardless of your taste, level of sophistication, or budget. Just as the vintage, the contemporary is finding a place adorning American bars, restaurants and mezcalerías. And, mezcal tourism is immune to the usual vagaries impacting travelers to Oaxaca. Those who typically visit to experience the state’s renowned cuisine, pristine beaches, archaeology, more traditional crafts, museums, vibrant marketplaces, the capital’s café-lined zócalo, and colonial architecture, change or cancel plans based on a media reports, typically making unwarranted decisions. Oaxaca’s economic fortunes are appropriated described in terms of extreme peaks and valleys: the 2006 civil unrest, the Mexican swine flu, the US economic crisis, the warring drug gangs, zika, and then the next report which is undoubtedly just around the corner. Most people forget a short while after each, and then there is another reminder to not visit Oaxaca. But those who come for mezcal appear to be a different breed of visitor. They take the media and their home country state department cautions with a grain of salt, and/or do their own more directed and detailed investigation. They come, and they spend. New markets for mezcal and consequently opportunities for its export are rapidly growing. And so there is a resultant dramatic influx of visitors wanting to take advantage of the boom. Both aficionados and those seeking business opportunities from France, England, Australia, South Africa, Panama and further down into the southern hemisphere, and many from other reaches of the globe, are all now picking up mezcal on their radar screens. And so at least for the next decade, industry growth and the related economic opportunities for Oaxaca, and indeed for other Mexican states legally able to call there agave spirit mezcal and thus export it, will continue to surge. Since 1991, Alvin Starkman has been a mezcal aficionado and student of its diverse and fascinating production methods and broad range of aroma and taste nuances. He operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com), imparting his knowledge on his clients, and literally bringing them into the worlds of the dedicated, hard-working, and now proud palenqueros and their families.

0 Comments

by Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. Second only to dark chocolaty mole negro, without a doubt tlayudas are the principal, uniquely Oaxacan culinary seduction, renowned throughout Mexico. While eaten virtually any time of day or night, tlayudas are more typically consumed late evenings, and tradition suggests that they be purchased from street vendors. Tlayudas México 68 is one such nighttime stand which has meteorically grown in popularity since its inception a dozen years ago. In 2006, Giezi was an 18 year old adolescent living with his family in Colonia Loma Linda, a suburb of the city of Oaxaca. He had been working at a nearby taco stand, when one day he began a discussing a business project with his mother, Alma. Within a few months the two of them opened Tlayudas México 68, in the Colonia Olímpica neighborhood of the city, close to their home. It was just Giezi and his mom. Tlayudas come in different incarnations, the only constant being the main ingredient, that is an oversized somewhat crispy all-corn tortilla, usually about a foot or more in diameter, with toppings and/or accompaniments. A single tlayuda constitutes a full meal, as distinct from tacos, tostadas and the like. It can be vegetarian, vegan, even kosher style, usually just for the asking. But the most common formulation is a very thin layer of pork fat (asiento), followed by a patting of bean paste, then Oaxacan string cheese (quesillo), and meat either inside the tlayuda or alongside it. Sometimes they are served open faced, and sometimes folded over in half. Often lettuce, tomato and avocado is included, but certainly not always. Typically condiments are served with it, consisting of salsa, guacamole, marinated onions and chiles, an aromatic herb (chepiche), and/or grilled onions. The meat is usually beef (tasajo or arrachera), pork (cecina), pork rib (costilla) or Mexican sausage (chorizo); less so shredded chicken. If ordered from a restaurant or roadside eatery (comedor), one can often substitute fried egg and/or mushrooms for the meat/cheese protein. Tlayudas are grilled over charcoal, either placed directly on the coals or on a grate above. For the asking your tlayuda can be custom designed. Tlayudas México 68 took off immediately. Until then there were very few nearby local haunts for getting tlayudas. There are many places downtown, as well as flecking different neighborhood streets in and near the city. But up that way, bordering the wealthy north suburb of San Felipe del Agua, and close to middle class Colonia Reforma and upstart Colonia Loma Linda, there really wasn’t much. And right around the time of the stand’s inauguration, Oaxaca was experiencing a great deal of civil unrest. Member of the working and upper classes were loath to venture downtown because of teacher protests and marches, road blockades, vandalism, and even nighttime tire fires in major city intersections often outright precluding the ability of residents to venture to the city’s core even if they wanted to. Giezi and Alma opened at the right place (on Calle México 68) at precisely the right time, and haven’t looked back. The complement of employees / business partners has grown substantially. Alma and two sisters stay at home in Loma Linda and daily prepare the salsas, guacamole and other accompaniments as well as fresh juices (aguas frescas; horchata and jamaica). Suppliers deliver all the other ingredients to the house which are needed for a late afternoon start-up, such as quesillo, raw meats (arrachera and costilla), tortillas and other corn products, fruit, vegetables, charcoal, etc. The stand begins set-up around 4:30 pm, and is open for business 7 pm to midnight, seven days a week. It is operated by ten people including Giezi and his wife, his four brothers and the wife of one of the brothers, and three friends who have day jobs; an accountant, a key cutter, and an ironworker. For the seven, this is their sole source of income. But they prepare for not just on the street where patrons can pull up a plastic chair to chat while awaiting what they have ordered. They also do take-out, home delivery, and events such as birthdays, anniversaries and school graduations. Giezi and one of his brothers split two week shifts. For one period Giezi works at México 68 while the brother does home deliveries and events, and then they switch jobs. They’ve done events where they’ve prepared as many as 1,200 tlayudas. While tlayudas are the mainstay, they also do a brisk business grilling tacos and tostadas. For take-out, the condiments are packaged in small plastic bags. For events, team members set up a veritable mini México 68 at homes, schools and event halls, bringing along their grills, charcoal, tables, and whatever else the client needs. It’s common to see more than a dozen cars, trucks and motorcycles parked along both sides of México 68, well into the night, seven days a week, drivers and their passengers awaiting their orders. Smoke billows from the grill, the quesillo is being shredded, the meats are being barbequed and then chopped, and finally the tlayudas are being armed together based on the wishes of the patron, folded, placed on the grill, and finally heated to perfection before being either served on a plate, or packed with condiments for take-out or home delivery. The logistics of it all? A member of the team connects to a hydro wire every night, with the permission of the neighborhood including the local church. For Giezi it’s crucial that their neighbors are treated with the utmost respect and deference. The city renews the on-street permit annually. All workers must attend for medical examinations twice yearly, and for training on sanitary food preparation and service. So now you know, at least should you venture to México 68. Giezi and family have considered opening a branch, but have so far resisted because of concerns about having non-family or friends as employees, and thus worrying about them not showing up for work, arriving late, or quitting without providing sufficient advance notice. And why even bother, when as in the case of Tlayudas México 68, patrons come from as distant as the outer reaches of the Etla villages and further beyond, often more than 40 minutes away, just to sit and eat tlayudas, tacos and tostadas, all prepared to order by their favorite nighttime stand. Alvin Starkman owns and operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com).

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

Why do many in the mezcal business, the self-aggrandized experts, and others supposedly in the know, shun the thought of drinking mezcal con gusano and any type of aged product be it reposado or añejo? More troubling is that many counsel imbibers against even touching to their lips anything but a blanco or joven (unaged) mezcal. This issue is particularly incomprehensive given that corn whiskies, brandies, scotches and some wines are aged in oak barrels. And, both internationally renowned chefs and acclaimed traditional Oaxacan cooks use the gusano del maguey or agave worm to flavor some of their culinary delights. In prehistoric times, that is prior to the mid 1990s, we were drinking relatively few types of mezcal. With nary an exception our options were essentially limited to unaged, reposado (aged in oak for at minimum a couple of months), añejo (aged in oak for no less than a year), “with the worm,” and if we were lucky we could put our hands on the occasional bottle of tobalá. Selection options are very different today, innumerable in fact. Many imbibers have either never known or forgotten that quality mezcal can come in several forms, including aged and infused. Mezcal con Gusano Mezcal con gusanso first appeared in the marketplace decades earlier than the modern era. It became popular on college campuses as a cheap way to get drunk fast because of its relatively high alcohol content, and of course the traditions and myths surrounding its imbibing carried its popularity forward. “The worm,” actually a moth larva which infests and attacks the root and heart of certain agave species [variously identified as Aegiale hesperiaris, Hypopta agavis and/or Comadia redtenbacheri] became a marketing tool for distillers, exporters, importers and distributors. But the infusion also changed the flavor of the mezcal into which it was inserted. Most gave short shrift to considering how the character of the mezcal was being altered, and would never consider this type of mezcal a fine sipping spirit. Perhaps back then it wasn’t. But what if today you enjoy the nuance of mezcal which has been infused with a gusano? A couple of years ago I took a bottle of mezcal con gusano off one of the shelves housing my collection of agave spirits. I slowly sipped it. The flavor shockingly reminded me of a couple of my favorite whiskies, peaty single malt scotches from Islay! Today there are good and bad mezcals with gusanos, with our assessments being based on subjective criteria, just as there are good and bad unaged mezcals. Quality may be impacted by, amongst other factors, the type of gusano (although it is typically one type used to flavor mezcal), how the larva has been prepared for infusion into the mezcal, the specie and sub specie of the agave used to make the base mezcal, and the skill of the artisanal distiller. The point is, that yes this type of mezcal was likely initially marketed with a view to increasing sales of the spirit because of its uniqueness, but we should give it a chance, just as we would sampling different joven mezcals. Not all mezcals produced with madrecuixe, tepeztate, jabalí, tobalá and espadín are the same. Some we like and some we don’t. You may find the same thing with mezcal con gusano. And if you find a couple of brands to your liking you may just stop spending $100 USD on a bottle of Lagavulin. So don’t write off mezcal con gusano just because at this moment in history it’s un-cool to like it, or your memory of it is clouded by what it meant to you years or decades ago. Mezcal Añejo Now the story of aged mezcal is entirely different, since long before the emergence of mezcal con gusano, añejos and to a lesser extent reposados were deemed quality sipping spirits. Thankfully in many circles they still are, and indeed many brands have been able to capitalize on the continuation of this perception. But since the early 2000s a movement has emerged, and seems to be gathering steam, dissing aged agave spirits, mezcal in particular. The rationale goes something like this: they are not “traditional” mezcals; aging masks the natural flavors of mezcals which are derived from an agave specie and impacted by means of production and tools of the trade, and microclimate; and the list goes on. Hence, we should avoid drinking reposados and añejos at all cost. The proponents of these lines of thought lecture about it, disseminate their position on their websites, and promote their “knowledge” in print, all purporting to promote the industry. What can be more traditional than a custom dating back hundreds of years? Depending upon the version of history to which one subscribes, the aging of agave spirits in oak barrels dates back to somewhere between the 1500s and the 1700s, and certainly not more recently. The oral histories I have personally taken are based upon elderly palenqueros having recounting to me from their own experience dating back to the 1940s. The current crop of brand owners and representatives were not even born then. The history of aging mezcal in wood actually begins with the Spanish arriving in The New World with brandy transported in oak casks. Many barrels remained in what is now Mexico. Even using the most recent dateline of the 1500s for the birth of distillation in Mexico, we find aging. Here’s why. At some point after distillers began producing agave spirits and storing and transporting them in clay pots, they realized that the capacity for transporting was restricted to about 70 – 80 liters because of the size of the receptacles. And since the pots were fragile they were prone to breakage. Oak barrels from initially Spain became available for the same purposes, that is, storing and transporting the spirit. They became preferred because they were larger and more break-resistant than the clay “cántaros.”So, if not by design then by default, palenqueros were aging their spirits in oak, long, long ago, and consumers were enjoying it. Aged mezcal is traditional. Query the purists who state that mezcal should only be stored in glass. Is glass traditional? No, clay is, dating earlier than oak. Clay too changes the notes of the agave spirit. Perhaps we should distinguish traditionalists from purists. But some of these same “experts,” the purist class, drink, sell and promote mezcal de pechuga. Typically this type of mezcal has been distilled a third time, during which there is generally a meat protein (chicken or turkey breast, rabbit or deer meat, etc) dangling in the upper chamber of the copper alembic or clay pot, over which the steam passes thereby imparting a subtle change in the spirit’s nuance. Most contemporary distillers insert a range of fruit, herbs and spices into the bottom pot while continuing to use the protein in the process. There are umpteen variations on the theme. In any event, the totality of these added products dramatically alters, and yes to a certain extent masks the natural flavor imparted by the particular agave specie, means of production and tools of the trade. Where aged agave spirit is not acceptable, mezcal de pechuga is, and is sold at handsome prices. Is there a disconnect? There are other rationale some use for urging spirits drinkers to not drink aged mezcal:

The recent promotion of mezcal based on specie and sub-specie of agave rather than the few categories noted at the outset, as well as on the particular village or district where the agave was grown and processed into mezcal, has helped the industry get to where it is today. But the downside has been that añejos have been left behind in the wake, and many who have become mezcal aficionados have not even had a chance to try aged product. And they wouldn’t even think of trying a mezcal con gusano. It just isn’t cool or acceptable in much of today’s world. Conclusion It’s time we begin to embrace diversity which includes gusanos, reposados and añejos, and either ignore the naysayers or better yet tell them that their opinions are no more valid than ours. If we, the imbibing public, try a mezcal with something in the bottle or a product that is not perfectly clear, and don’t like it, we may not try it again, or we may sample from a different brand or batch. But don’t even suggest that it isn’t traditional or of good quality. Let us be the arbiters. Retailers, mezcalerías and tasting rooms, should consider carrying initially at least a bit of those products so we can make our own decisions. Otherwise they are doing a disservice to those producers who are continually working hard to trying to create more pleasantly palatable and diverse mezcals, and just as importantly they are restricting the options of their own clientele, without valid reason. Alvin Starkman owns and operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). He has a collection of more than 400 different mezcals, with con gusano, reposado and añejo housed alongside his single malt scotches. Lidia Hernández Baneza García Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

A characteristic of growth in the global wine industry for some decades is slowly creeping into artisanal mezcal production in the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca. That is, small producers are using their new-found disposable income to educate their children, with a view to increasing manufacture in a sustainable fashion while at the same time improving sales through tapping new markets. Oaxaca is where most of Mexico’s mezcal, the typically high alcohol content agave-based spirit, is distilled. In the early years of this decade the state began to witness a dramatic increase in sales of mezcal, both in the domestic market and for export to the US and further abroad. Mezcal tourism was born. Visitors began to make a pilgrimage to primarily the state capital and its central valley production regions, coming to learn about artisanal production, to sample and buy for home consumption, to educate themselves and their staff with a view to attracting sales at bars and mezcalerías, and to consider a business plan for export to foreign and to non-Oaxacan Mexican markets. Lidia Hernández and Baneza García are representative of this sweeping new trend in Oaxacan mezcal production, not because they are young women (in their early twenties), but because of education. In both cases their parents, integrally involved in family artisanal distillation dating back generations, did not progress beyond primary school. Ms. Hernández has recently completed law school at the state run university and Ms. García is in third year industrial engineering at a private college. Both, however, work in the mezcal business and are using their education to advance the economic wellbeing of their respective families, and to preserve and improve the industry. And of course as is typical in virtually all families which produce artisanal mezcal, both began learning how to make the spirit at a very early age, literally upon taking their first steps. The impetus for the meteoric growth in the industry occurred in the mid-1990s with the introduction of Mezcal de Maguey’s brilliant “single village mezcal” marketing, with other brands following suit (i.e. Pierde Almas, Alipus, Vago). Virtually all artisanal producers began experiencing a dramatic increase in sales. Initially the new-found wealth meant the ability to buy toys such as flat screen TVs, new pick-up trucks and the latest in computer technology. But then a curious phenomenon began to emerge in families, not only those with ready access to the export market, but those in which domestic sales had begun to skyrocket. More families began perceiving the value in higher education, creating opportunities both for their children and for their own advancement. Therefore they began to divert funds in this new direction. To best understand the part these two women have already begun to play in the mezcal trade, we must step back several years to industry changes which began to impact the Hernández and García families, and of course many others. But before doing so we should note that lawyers don’t just learn the law, and industrial engineers don’t just learn how to design buildings and factories. Higher education impacts the ways in which we think more generally, how we process information, our spatial perception of the world, as well as about options for dealing with change and adaptation. But still the pedagogic strategies these women have been learning are rooted in their particular disciplines. And while palenqueros with a lack of formal education do not necessarily understand the intricacies, niceties and full impact of the foregoing, at least today in Oaxaca they do get it; that is, the broad though not fully digestible positive implications for the family of supporting higher education of their progeny. If we accept that it takes an average of eight years to mature an Agave angustifolia Haw (espadín, the most common type of agave used to make mezcal) to the point at which it is best harvested to be transformed into mezcal, and that it was only about 2012 that producers, farmers and brand owners began to in earnest take notice of the “agave shortage” (more appropriately put as the dramatic increase in price of the succulent), then we are still a couple of years away from being inundated with an abundance of the agave sub specie ready to be harvested, baked, fermented and distilled. The phenomenon has been created by both businesses from the state of Jalisco sending tractor trailers to Oaxaca to buy up fields of espadín, and the mezcal boom. The latter has resulted in many palenqueros of modest means all of a sudden experiencing a dramatic increase in sales and corresponding extra income for the family, albeit now having to pay much more for raw material. Communities are struggling with waterways above and below ground being chemically altered by distillation practices and wastewater, wild agave being stripped forever from landscapes, and several aspects of sustainability. At the same time regulatory stresses abound; from discussions with palenqueros and others in the industry, it is clear that the Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (the mezcal regulatory board, or CRM) is exerting pressure by “encouraging” palenqueros to become certified, and whether by design or not then adversely impacting those who do not comply by making it more difficult for them to eke out a living selling the distillate. The movement has been spearheaded by those who believe that uncertified agave spirit should not be termed “mezcal” nor sold and certainly not exported as such. It is of course trite to suggest that there are implications regarding taxation. Lidia Hernández’s parents are in their early 50s. They have three children aside from Lidia, and all help in the family business; 30-year-old Valente lived in the US for a few years then returned home at the request of his mother and is now a full-time palenquero, 27-year-old Bety is a nurse who helps out with mezcal on her day off, and 16-year-old Nayeli is in high school in an education system known as COBAO, a hybrid between public and private to which many bright students in rural communities have access. While Lidia is writing her law school thesis she is working in the family palenque in Santiago Matatlán full time. After completing her dissertation she intends to continue on with mezcal until she believes that her expertise is no longer required on a continual basis. Even then, she will use her skills to advance the economic lot of the family. Lidia attended public school. While initially she was interested in history and anthropology, because Oaxaca did not offer that program at the university level she opted for law. “I wanted to help people, to defend them because regular Oaxacans are really not very good problem solvers, at least when it comes to dealing with the law, police, family issues, business plans, and so on,” she explains. By age eight she had learned about and participated in virtually all steps in mezcal production. Early on she realized she could help grow the family business, using her new skills to help navigate through the rules and regulations in a changing mezcal industry. For in excess of the past year she has been:

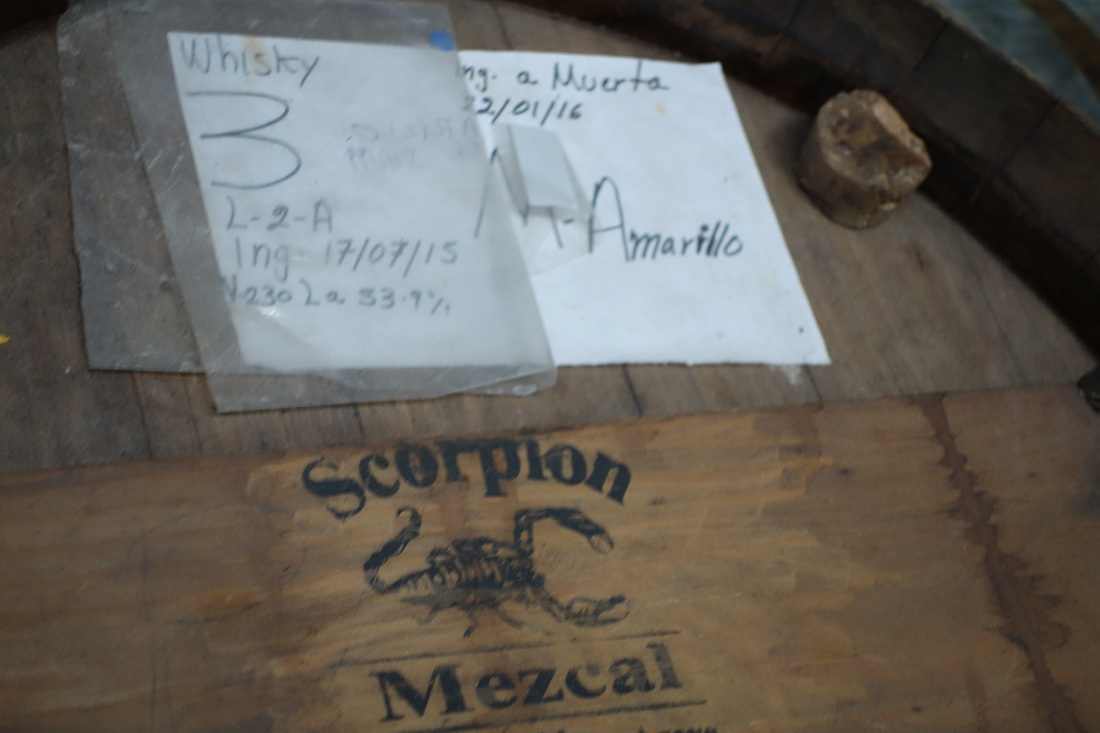

Lidia sums it up: “Of course down the road once all is in order and the family business is certified and is running more efficiently and productively, and profitability is where we think it can be, I’ll get a job working as a lawyer, perhaps for government; but I’ll always be there for my family and continually strive to help produce high quality mezcals at market driven prices.” Baneza García’s mother is 43. Her father died of alcohol related ailments three years ago at age 40. There are six children in the family ranging in age from 9 – 25. The two youngest are in primary and junior high and the next oldest attends high school at a COBAO. The eldest completed junior high and now works in the family tomato growing business. Baneza and a younger brother attend a private university just outside of the city, both studying industrial engineering. Baneza is in third year of a five year program. She and her brother rent an apartment close to school, but return home to the family homestead in San Pablo Güilá on weekends and for holidays. The extended family all helps out in the mezcal business which was started in 1914 by Baneza’s great grandfather. The family includes her aunt and uncle who are slowly assuming more responsibility, yet are still learning from Baneza’s grandfather Don Lencho. The García family’s palenque became certified a few years ago, when an opportunity arose to sell mezcal which now reaches, of all places, China. More recently Baneza and family have been working with a different brand owner to produce mezcal which they are on the cusp of bottling and shipping to the US. The Hernández and García families are in very different circumstances. Nevertheless, there is a common thread in the education of both Lidia and Baneza; utilizing the skills and opportunities to ultimately advance their respective family businesses. Baneza is interested in both improving efficiency in her family’s mezcal production, and reducing adverse environmental impact of traditional practices. With regard to the former, although her family is still resistant to the idea, she is interested in giving more thought to replacing horsepower currently used to crush the baked sweet agave, with a motor on a track directly above the tahona, similar to that employed in other types of Mexican agave distillate production. The heavy limestone wheel and shallow stone/cement pit would remain thereby not altering flavor profiles, often the result when for example metal blades in an adapted wood chipper or on a conveyer belt are employed. Regarding environmental impact, Baneza is working on ideas to transform otherwise waste product such as discarded agave leaves and the spent fiber produced at the conclusion of distillation, into commodities of utility. Both materials have traditionally found secondary and tertiary uses (i.e. the latter, that is the bagazo, being used as compost, as mulch, as a principal ingredient in fabricating adobe bricks, for making paper, and as the substratum for commercial mushroom production); but the bounds of ingenuity are endless, especially as learned in the course of a five year program in industrial engineering. The family has already adopted Baneza’s suggestion for recirculating water in the distillation process, rather than the more costly and typical (at least when water was not as scarce a commodity) practice of simply discarding it. The application of Baneza’s classes in industrial psychology will have a long-term effect on how her family views its place in Oaxacan society: “It’s a matter of convincing my family, through discussion, illustration and perhaps trial and error, that there are many ways to improve production which will ultimately lead to an easier and more self-fulfilling life for me and my relatives, and better sustain our industry.” Lidia Hernández and Baneza García are not alone. They are representative of a much broader trend. Both young men and women who are children of palenqueros without higher education, exemplify change in the Oaxacan artisanal mezcal industry. I have spoken with students and graduates in business administration, tourism, linguistics, amongst other university programs, and their stories are similar: help the family artisanal mezcal business in Oaxaca. Then, down the road embark upon an independent career while maintaining an integral connection with the family’s spirit distillation. In 2014, while attending meetings of the American Craft Spirits Association and then the American Distilling Institute, master mezcal distiller Douglas French began to question why whiskey was not being produced in Oaxaca. After all, he pondered, the southern Mexico state had been acknowledged as the birthplace of corn, its domestication dating back somewhere between 11,000 and 14,000 years (depending on to which research one subscribes), with native strains still being cultivated today. Mezcal of course is the agave based Mexican spirit most of which is distilled in the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca. And French is best known for his internationally distributed Scorpion Mezcal, launched two decades ago when artisanal mezcal was virtually absent in the American marketplace, and to be sure, not on the radar of most spirits enthusiasts, even tequila aficionados. It was a combination of both fortuitous circumstance and some unproductive conduct by individuals in the administration of the Mexican agave spirits industry, which resulted in what had long been overdue; the birth of whiskey distilled in Oaxaca – under the name Sierra Norte Single Barrel Whiskey. French’s mezcal distillery had the space to augment output and to diversify production as his American counterparts had been doing; he had been buying used equipment at auction and in the open marketplace at a furious pace yet uncertain as to its use in his mezcal production; and he became concerned about the skyrocketing price of agave as a consequence of both mezcal’s increasing global popularity and tequila producers buying Oaxacan raw material and earmarking it for the state of Jalisco’s tequila country. While French had hectare upon hectare of agave under cultivation, he was worried about being able to maintain competitive retail pricing if he was required to buy agave in the open market at inflated prices. Finally, with aged mezcal being both out of vogue and unfashionable having not yet been “discovered” by neophyte mezcal aficionados jumping on the bandwagon, what to do with some 400 oak barrels. So French began learning about whiskey, and experimenting with its production. While some of his existing equipment could be used in his new operation, and part of his aging stockpile of scrap metal could be adapted, he did have to invest in milling, mashing and filtering equipment not employed in mezcal production. All was proceeding fairly well. But then beginning in August, 2015, and continuing for seven months, Scorpion was unable to supply its mezcal to its global retailers. French retooled. He cut hours of employment and salaries in half. In order to remain in business he had to. His employees had been being paid enough during regular times so as to enable them to survive and remain loyal to him. His unwavering commitment to the employment of women, predominantly single mothers, has been chronicled elsewhere. Not able to ship mezcal, together with his faithful team he spent his time working on whiskey recipes, fabricating optimum equipment, branding Sierra Norte, sourcing native strains of corn in the villages, and planting it with the assistance of a team of ten male workers. French’s Sierra Norte Single Barrel Whiskey is currently entering the US in three formulations, each matured in French oak casks so as to showcase its individual character and nuance; yellow corn, white corn and black corn, with red corn around the corner. He continues to work on recipes for additional whiskies, as well as for other spirits, but out of respect for French and journalistic integrity I have decided to keep details of these new projects under wraps. He expects that within two years his gross revenue will have doubled its previous high, meaning more work for more women, perhaps even some of the progeny of his devoted female staff. French currently employs in his distillery on a full-time basis two men, and ten women, one of whom has been working continuously for 34 years, for French and before him for his late mother Roberta in the textile industry. Another has been with him for 24 years including four years prior to when French began distilling on his own and while he also was producing textiles for export. Douglas French is likely the only American – born mezcal distiller in the state of Oaxaca; and now his wonderful whiskies, shockingly unheard of until now. His dedication to his trade as a distiller and as an employer of women in an industry dominated by male workers, is steadfast. Perhaps history is repeating itself. It has been suggested that the promulgation of the North American Free Trade Agreement had an adverse impact on many small producers in the Mexican textile industry and that more generally 70% of Mexican industry was required to close because of it. In the wake of NAFTA, while struggling in the textile manufacturing business French found a way to keep himself and his staff above water, and in fact grew Scorpion Mezcal into a force to be reckoned with in the spirits market. And now, decades later, Scorpion has survived, and indeed thrived despite a dramatic increase in brands resulting from the recent mezcal boom and despite not being able to ship mezcal for more than half a year. What Scorpion did for French and staff previously in the textile business, Sierra Norte Single Barrel Whiskey is doing for them now. Growth and prosperity is returning. Whiskey will likely never displace mezcal, either in Oaxaca or elsewhere in the country. But if pioneer and resilient innovator Douglas French has his way, the 2016 launch of his Sierra Norte Single Barrel Whiskey will at minimum have an impact on the retail spirits market both in the US and further abroad. Down the road this will undoubtedly mean growth and prosperity for French, his staff, and spirits production and producers throughout Mexico. Sierra Norte Tasting Notes Compiled by Thom Bullock, Chef Pilar Cabrera and Alvin Starkman Yellow Corn Whiskey: Nose – notes of toasted corn, buttery popcorn with a hint of caramel Palate – relaxed pleasing and extremely smooth with mellow grilled pineapple and subtle red chili spice Finish – long and warm with honey, allspice and ash White Corn Whiskey: Nose – vanilla, almond and black squid ink with a subtle undercurrent of gym shoes Palate – tones of green apple accented with metallic / lead Finish – smooth with cinnamon spice Black Corn Whiskey: Nose – penetrating maraschino cherry and banana peel Palate – deep ripe plantain Finish – wedding cake with almond vanilla icing Alvin Starkman owns and operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (http://www.mezcaleducationaltours.com).

Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

It’s hard to separate fact from fiction from fear-mongering, when trying to understand the relationship between the Mexican agave-based spirit mezcal, and methanol poisoning resulting in blindness or death as the worst case scenarios. The purely physical science treatises are in large part beyond my level of comprehension. At the other end of the spectrum one finds lay literature without references backing up claims and allegations regarding the likelihood of hangovers, headaches and the much more serious harmful effects; it’s all cloaked in words and phrases like “as little as,” “likely” and “probably.” And it ignores aspartame. Introduction Is it appropriate to equate mezcal which has been produced essentially safely and without incident by families in the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca for generations, with American moonshine, with deaths due to deliberately adulterating a spirit for purely profit motive, with concoctions created by naive youth, or with reports from third world countries in which ignorance of safe spirit production results in imprudent means of production or the use of equipment which contaminates? It is suggested that the alarmists draw their data from such sources. For the past 25 years I’ve been drinking mezcal sold at small, family owned and operated artisanal distilleries (palenques as they’re known in Oaxaca), without incident. And so have my Oaxacan friends and compadres, hundreds of thousands of villagers who have been patronizing their neighborhood producers (or palenqueros), and more recently visitors to Oaxaca anxious to sample and take home what they cannot find at their local bars or source from retail liquor outlets. Otherwise all I have to rely on is my cursory review of online literature (including but not restricted to International Center for Alcohol Policies, UPI, Methanol Institute, National Institute of Health / U.S. National Library of Medicine, World Health Organization; a list of references consulted is available upon written request), and my background in social anthropology. It was my Darwinian academic training which lead me to an internet search so that I might be able to prove what I considered to be a reasonable hypothesis, and put into perspective the tall tales I’d been reading. Regarding the latter, I have read that mezcal not certified by a regulatory agency is fake, illegitimate, results in hangovers, and may even lead to blindness or death from methanol poisoning. Have imbibers of agave-based spirits been extremely lucky all these years, decades and perhaps even millennia? The two lines of thought regarding the origins of distillation in Mexico are that indigenous groups learned to distill long before the arrival of the Spanish, or, that the Spanish learned distillation from the Moors and so brought that knowledge with them in the first half of the 16th century. The former theory gives more credence to my thought process, although 450 years of trial and error and perfecting safe distillation is nothing to sneeze at. Just like the early Zapoteco natives of Oaxaca learned to dye with the cochineal insect, and in due course presumably through trial and error that the mineral alum served as the best available mordent or fixer, it is suggested that so too did the invaders and the indigenous peoples of Mexico learn how to distill safely. Following the same analogy, it is likely that long ago wool dyed red with cochineal dramatically faded from the sun or through washing, until the best available mordent was found; and so perhaps dating back hundreds of years indeed native Mexicans (and Spanish) succumbed to unwise distillation practices. They have learned the benefit of using alum; and of taking off the methanol, and using predominantly clay or copper or other “safe” metal compounds during and for distillation respectively. Methanol Explained Even the healthiest among us, and that includes those who do not imbibe alcohol, have methanol in their bodies. Humans get it in small amount from eating fruits and vegetables. It is not only absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, but also through the skin and by inhalation. Methanol is metabolized in the liver, converted first to formaldehyde, and then to formate (formic acid). As a building block for many biological molecules, formate is essential for our survival. On the other hand, high levels of formate buildup after excessive methanol intake can cause severe toxicity. An EPA assessment reported that methanol is considered a cumulative poison due to the low rate of excretion once it is absorbed. The primary uses of methanol are for industrial and automotive purposes. It is found in antifreeze, canned heating sources, copy machine fluids, de-icing fluids, fuel additives, paint remover or thinner, shellac, varnish, windshield wiper fluid, and more. This is known as denatured alcohol. Government regulations in fact dictate the inclusion of high levels of methanol as a compound in such products, knowing its toxicity and wanting to ensure that the public buys its liquor (in which levels of methanol are controlled, as opposed to other alcohols), in order to maintain healthy tax revenue. But Government dictates do not prevent the drinking of denatured alcohol or it being used to fortify other beverages. In fact the literature on non-commercial alcohol, which is sometimes referred to as unrecorded alcohol, cites these “surrogates” or non-beverage alcohols, as one of three categories of drinks which potentially create health risks. They are drunk alone (i.e. the classic skid row cases), and used as “cocktails” when they are added for example to fruit juices. The other two are “counterfeit” products and illicit mass-produced drinks, and traditional drinks produced for home consumption or limited local trade (licit or illicit). It is suggested that artisanal mezcal falls into the second part of this third category. So yes, there is the possibility of health problems arising as a consequence of consumers imbibing Mexican mezcal with higher than “safe” levels of methanol. Spirits Health Risks in Mexico and Internationally In central Mexico, as born out in the literature, much more than anything else the singular health problem related to mezcal and other traditional alcohol consumption is alcoholism resulting in liver cirrhosis. In an article centering upon global methanol poisoning outbreaks, the World Health Organization cited examples of adulterated, counterfeit and informally produced spirits in Cambodia, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Libya, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Turkey and Uganda. Mexico is conspicuously absent from the list. In an article centering upon the quantification of selected volatile constituents in the Mexican spirits sotol, bacanora, tequila and mezcal, while methanol was the most problematic compound and at times the samples taken were far above the levels recommended by international as well as national standards, two points are particularly noteworthy: methanol levels were not of toxicological relevance; and, other legally obtained drinks such as German fruit spirits were found to have significantly higher methanol levels. In an article entitled “Noncommercial Alcohol: Understanding the Informal Market,” the International Center for Alcohol Policies reported that much of the perceived health risk stems from patterns of drinking such as chronic consumption and binging, use of low quality ingredients, adulteration, and lack of control during production or storage. In Russia and other republics in the former Soviet Union samagon is cheap and easy to make using household equipment. Kenya’s poor fortifies its grain spirit, chang’aa, with surrogates. Brazil’s national drink cachaca or pinga is sometimes fortified using industrial alcohols, some of which have been noted above. And what about the United States’ renowned moonshine, the usually high alcohol content spirit typically made using corn mash as the main ingredient? Poorly produced moonshine is contaminated mainly from materials used in still construction, such as employing car radiators as condensers (glycol from the antifreeze or lead from the connections). In addition, methanol can be added to the spirits to increase strength and improve profits. The 1994 reported poisoning from ingesting mezcal produced in the Mexican state of Morelos cite the spirit having been spiked with methanol. It is suggested that this was an aberration, though of course is noteworthy. Somewhat surprisingly, there was relatively little reported about the incidents, and they have not to my knowledge received attention in the broader English literature centering upon methanol poisoning. As suggested, methanol is not the only potentially harmful constituent. Lead as well as other toxic metals can poison not only as a consequence of employing unsuitable distillation equipment but also through the use of a contaminated water source. Volatile compounds such as acetaldehyde or higher alcohols can be produced in significant amounts due to fault in production technology or microbiological spoilage. There have been occurrences of certain fruit and sugarcane spirits containing the carcinogen urethane. When is Methanol Safe? Returning to methanol, one must now ask what is the safe maximum level of its ingestion. It was only in 1981 that the sugar substitute aspartame was approved for dry goods, and two years later for carbonated beverages. It is made up of three chemicals: aspartic acid, phenylalanine, and methanol which makes up a whopping 10% of its composition. The absorption of methanol into the body is sped up when “free methanol” is ingested, and this form of the chemical is created from aspartame when it is heated to above 86 degrees Fahrenheit (i.e. when making sugar-free Jello). In 1993 the FDA approved aspartame as an ingredient in numerous food items that would normally be heated to above that temperature. The EPA recommends consumption of no more than 7.8 grams of methanol daily. While the amount of aspartame in a diet soda can vary, it has been reported that a single can produces 20 mg of methanol in the body. It is no wonder that aspartame accounts for over 75% of the adverse reactions to food additives reported to the FDA. Chronic illnesses can be triggered or worsened by ingesting aspartame. The range of afflictions reported is alarming. The current regulation for the maximum amount of methanol in mezcal is .3 of a gram per 100 ml. It is an arbitrary standard. Query how much mezcal one must ingest to reach the EPA maximum limit of methanol of 7.8 grams daily. The FDA states that as much as .5 of a gram per day of methanol is safe in an adult’s diet. Should the Mexican standard be higher, or lower? It is no wonder that the study referenced earlier identifying volatile constituents in Mexican spirits, did not find toxicological relevance in the face of analyzing samples far above recommended levels. Furthermore, as distinct from household foodstuffs and drink containing aspartame, ethanol (i.e. mezcal) serves as an antidote for methanol toxicity in humans. Conclusion There is indeed confusion in the literature regarding recommended maximum levels of methanol and at what level health risks kick in, both dealing specifically with Mexican spirits, and where they are noted merely tangentially or not at all. However there is also considerable consistency: Aside from my Darwinian suggestion that the days of dangerous mezcal production have long passed, and acknowledging the issue of still construction, it is noteworthy that almost all artisanal distilleries in Oaxaca consist of either copper alembics or similar production equipment made in equally standardized and carefully monitored workshops and factories; or in clay pots. In both cases they are essentially free of harmful levels of chemical compounds. If there is a lesson to be learned, it is perhaps that one should never drink artisanal mezcal, commercial or otherwise, while consuming government authorized products containing aspartame. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (http://www.mezcaleducationaltours.com), a registered trademark. He is authorized to teach about the culture of mezcal and pre-Hispanic beverages by the Mexican government. Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

The branding of Kimo Sabe mezcal is brilliant. Perhaps not since the mid 90s when Ron Cooper coined the phrase Single Village Mezcal for his Mezcal del Maguey, has anyone used a name so effectively to attract a particular demographic in the alcohol buying public. Back then it was a take-off on single malt scotches. Now it’s addressing those of us in our sixties who recall the weekly TV show, The Lone Ranger, affectionately known by his sidekick Tonto as Kimo Sabe. Most, however, don’t know that its literal translation is something like “trusted friend.” The name nevertheless calls us, despite the fact that when I first heard it I thought there could not have been a hokier moniker on the planet. I couldn’t have been more wrong, at least from a marketing perspective, especially after I understood what the brand owners, at least in my mind, are trying to achieve. The peace and love generation has finished raising its children and put them through college, paid off mortgages and retired other debt, all the while having forgotten about the counter-culture. It sold out to become part of the corporate and professional western world. But there has been a significant positive: its members now have sufficient disposable income to spend as much as they want on whatever they want. Enter mezcal, taking us back to our roots, that is our desire for something real, natural and organic, reminiscent of what back then we coveted but couldn’t afford. Sure, there were Birkenstocks. But unlike a bottle of $200 USD mezcal (not Kimo Sabe), they didn’t empty and then require replenishing. I’m asked at least twice monthly, why only now is there a mezcal boom, when the spirit has been around for some 450 years, if not longer. My retort has been pretty standard, citing the hippie generation, the values of which were consistent with the production of artisanal mezcal. But back then we couldn’t afford to put our dreams, our words and our passions into action. Now we can, and we do. Not me literally, since I live and breathe mezcal and don’t have to pay what Americans customarily fork out. And it’s even more costly for those who live across the pond in the UK, or worse yet Australia. And so it appears to me that the makers of Kimo Sabe are targeting my generation, though probably not the higher end purchasers since the price-point of Kimo Sabe is extremely attractive. Why else select a name that conjures that era of B & W shows on an Admiral television built into a console? The brand recently took first place in a spirits competition, even ahead of quality tequilas. It won “Best of Class International Specialty Spirit” judged by the American Distilling Institute. But Kimo Sabe may just be a flash in the pan. I haven’t tried it so am not in a position to proffer an opinion. But I’ve been around the mezcal industry long enough to know that winning a competition is at least occasionally the result of no more than building relationships, and at times payola in one form or another, definitively not suggesting that this is the case here. Let’s just hope that would-be mezcal aficionados just don’t end up being tontos, and that Kimo Sabe ends up being a trusted friend of throngs of spirits consumers, both first time imbibers and those with a discerning palate. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (http://www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). He has a personal collection of over 330 mezcals from a diversity of regions in Oaxaca and from further beyond. Inquire about his full day personalized excursions. For a half century if not longer, the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca has been known in the US and further abroad for its high alcohol content, agave based spirit, mezcal. The region’s pre-Hispanic ruins, colonial architecture, cuisine and craft villages have been noted in travelogues and guide books for some time; but recently the iconic Mexican drink has taken center stage, and hence the arrival of mezcal tourism. It has gripped Oaxaca, and along with it, a revival of the chango mezcalero.

Chango mezcalero is a clay receptacle in the shape of a monkey, generally a liter in size or smaller. Traditionally, and arguably dating back to the mid-1800s, it was used as a bottle to market and sell mezcal. It was a natural, since the primate has been associated with drunkenness for eons. In the second of three articles authored by the writer, its history was dated to the 1930s based on uncovering a chango mold dated July 12, 1938, owned by the late Juventino Nieto of the Oaxacan town of San Bartolo Coyotepec. In a cardboard box alongside it was a somewhat larger undated chango mold of the same vintage. Don Juventino was the husband of the late Doña Rosa Real of black pottery fame. However, an alternate theory of the inventor of the chango, from the same village, has been put forward by members of his family. Many of the old chango mezcaleros found today have written on the back, Recuerdo de Oaxaca (souvenir of Oaxaca), some have a couple’s first names on one side or the other (celebrating their marriage), and most but not all are multi-color, painted with the gloss in various stages of decline. For the past couple of decades, and likely longer, vintage chango mezcaleros have become highly collectible, mainly by Americans interested in one or more of Mexican folk art, non-human primate imagery, and mezcal and its associated appurtenances. “Old” clay monkey bottles are available on ebay, and on other websites specializing in the purchase and sale of vintage Mexicana and what are otherwise known as “smalls” from Mexico and the southwest US. Prices can be as low and $50 and as high as $500 USD. It’s very difficult to discern whether or not a chango mezcalero was indeed made in the 1930s or earlier as some are represented. Antique dealers and aficionados know best how to date collectibles. Most in the general public, however, do not have a clue, and if it looks old to them, it is. There are currently at least three pottery workshops in the town of Santiago Matatlán which have been producing chango mezcaleros for decades, and continuing to date. Matatlán is known as the world capital of mezcal, boasting the globe’s highest number of artisanal (and at least somewhat industrialized if not more so) small family owned and operated distilleries, or palenques as the traditional ones are locally known. Some of these contemporary changos are upright, others are sitting on a log, and all are formed with the monkey in different poses. Until recently, if the changos were painted, and most of the time they were, they were glossy. The older ones, both tucked away gathering dust in the back of a palenque, and in local purchasers’ homes having been used, often show nice wear. As of early 2016, or thereabouts, vintage looking changos have begun to appear in the marketplace in Oaxaca. They have been spotted in at least one antique shop and one mezcalería. The coloring and patina is matte, and exquisite. There are at least two sizes. Most likely they are coming from the same workshop, using the same or similar molds as the shiny bottles, as is easily borne out by anyone who places the old and the new vintage side by side. It is not suggested that the retailers noted above are motivated by misleading or defrauding the buying public, despite the fact that some are for sale in an antique store. On the contrary, of those found in the latter outlet, some but not all are marked with the date 2015. Visitors to Oaxaca and elsewhere in Mexico, collectors surfing the net, and retail shoppers in the US and further abroad , should all be vigilant, and not be misled by the outward look of years of use. Oaxaca’s chango mezcalero has now come of age as a much more popular collectible than previously. Congratulations are indeed in order to the workshop which has identified the market. Alvin Starkman operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (http://www.mezcaleducationaltours.com). Alvin has been collecting chango mezcaleros for the past decade. He has been a permanent resident of Oaxaca since 2004. Oaxaca is known for mezcal. For decades the southern Mexico state has also been known for its beaches, craft villages, pre-Hispanic ruins, cuisine and colonial architecture. Oaxaca had three hotels ranked in the tripadvisor.com 2016 Travelers Choice Awards in the category of top 25 bargain hotels in the country. But for a state which relies almost entirely on tourism for its very existence, that’s not enough, relative to the Tripadvisor rankings for Mexico as a whole. And if it were not for the beach resort towns of Mazunte and Huatulco, Oaxaca would have been almost shut out entirely. Tulum, by contrast, has come out of nowhere to rank first of the top 25 world destinations on the rise. Can mezcal turn Oaxaca’s tourism fortunes around? Certainly its other attractions have not kept the state a force to be reckoned with in the rankings, where it arguably should be.

Tripadvisor.com is the world’s largest and most respected international travel website. Annually it publishes Travelers Choice Awards for the world, individual countries and regions, in several categories ranging from different classes of lodgings, to restaurants, to museums and other attractions. At least in the city of Oaxaca, mezcal tourism has taken off since about 2014, with a dramatic rise in the influx of visitors seeking out the spirit. They come from the US, Australia, other states in Mexico, Canada, the UK, and elsewhere. They are represented by:

Oaxaca failed to rank at all in the categories of Top 25 Best Hotels (number one spot taken by Rosewood Mayakoba in Playa del Carmen), Top 25 Luxury Hotels (top 25 number one spot taken by Rosewood Mayakoba once again), and Top 10 Fine Dining Restaurants (number one spot taken by Bravos Restaurant Bar in Puerto Vallarta). Surprisingly, internationally respected Oaxacan chef Alejandro Ruíz’s Casa Oaxaca restaurant failed to place in the rankings. It’s fairly safe to assume that the vast majority of tourists seeking out mezcal in the city of Oaxaca dine at Casa Oaxaca, yet the restaurant did not rank in the popularity contest. Perhaps mezcal aficionados do not use and are not registered members of tripadivsor.com, to the extent of other tourists with more generalized travel and vacation motives. While mezcal tourism cannot be expected to raise the reputation in all categories listed by tripadvisor.com, the entire state’s malaise is evidenced by virtue of the fact that Oaxaca fails to rank at all under Top 25 Family Hotels (number one spot taken by Paradisus Playa del Carmen La Esmeralda), Top 25 All Inclusives (number one spot taken by Le Blanc Spa Resort in Cancun) and Top 10 Beaches (number one spot taken by Playa Paraiso Tulum). While top spot in the bargain hotel category was taken by Hotel La Quinta del Sol in Punta de Mita, Huatulco hotels ranked numbers two and 23 for Misión de los Arcos and Hotel Villablanca Huatulco respectively. Posada Ziga in Mazunte was number 21, rounding out the state of Oaxaca’s respectable showing in the category. What’s interesting about these coastal resorts relative to mezcal tourism, is that one often hears complaints that it is difficult to find a good diversity of mezcal anywhere along Oaxaca’s Pacific shores Most mezcal aficionados who visit Oaxaca in fact do forego a beach portion of their vacation regardless of whether the visit is entirely for pleasure, or for business; though some in the former category combine culture and beach. Mazunte shone as well in the category top small hotels, taking number seven spot with Casa Pan de Miel (top spot went to Hacienda de Los Santos in Alamos, with number 12 going to Hotel Casona de Tita in the city of Oaxaca). Mazunte took second spot for romance hotels with OceanoMar, losing top spot to Le Blanc Spa Resort in Cancun. Nearby Huatulco ranked number 20 in the category top 25 hotels for service with Misión de Los Arcos, with, yet again Rosewood Mayakoba taking top spot. That’s three top rankings for Rosewood Mayakoba in Playa del Carmen, for best overall, luxury and service! Yes, Hotel Casona de Tita is a quality lodging in downtown Oaxaca, but it’s not very often that visitors interested in learning about mezcal stay there; only one high end hotel in the tripadvisor.com rankings for the city does not really impact anything. Rounding out the lodging categories, Oaxaca ranked number 12 out of 25 for best B & Bs and inns, for Casa Kei in Puerto Escondido, with top spot going to The Diplomat Boutique Hotel in Mérida. The state also had a showing in the museums category with the capital’s Museo de las Culturas taking number six spot, with naturally top spot going to Mexico City’s world acclaimed National Museum of Anthropology. The implication of the foregoing is that the state of Oaxaca has a lot of catching up to do with the Yucatan Peninsula. The latter boasts Tulum, Puerto Morelos, Cancun and Playa del Carmen. Granted, aside from hurricane season the Gulf of Mexico boasts better and more predictable weather than the Pacific. But that is no excuse for travelers’ choices in quality, especially when one considers mezcal tourism. And while Oaxaca’s civil unrest of a decade ago still weighs on the minds of some prospective visitors to Mexico, this should only reduce the numbers, and not significantly impact rankings relative to other tourist destinations in the country. Visiting Oaxaca? I suppose travelers should head to either Mazunte or Huatulco, at least for a southern beach-style vacation. But as suggested, Oaxaca’s coastal destinations will not get you much in the way of quality mezcal. The city must do a better job of promoting the spirit on the international stage. With at least 15 mezcal bars in a city of about 400,000, and aficionados converging from all corners of the globe, surely something is amiss. Let’s see if there is a change in the rankings for the 2017 tripadvisor.com Travelers Choice Awards. The number of mezcal bars, or mezcalerías, in Oaxaca, has exploded over the past couple of years. These watering holes cater to locals, Mexicans from the furthest reaches of the country, and of course to international tourists. While “mezcal tourism” has been and will likely continue to be a significant boon to Oaxaca’s economy, a frequently asked question is if the number of retail outlets in the city has reached the saturation point despite the recent dramatic rise in mezcal’s reputation on the world stage.

Tourism in Oaxaca, in general, has had its peaks and valleys since 2006, especially in terms of visitors from the US. That year witnessed significant civil unrest, and despite the fact that it was not dangerous for travelers to visit Oaxaca, the US state department warned against stepping foot in the state. Media also played a significant role in deterring tourism. Thankfully people’s memories are short, so tourism returned. That is until the “Mexican” Swine Flu scare. But tourism rebounded. Then there was the combination of the “Mexican drug wars” and the US economic crisis. But since the resurgence of the US economy, and President Peña Neto apparently taking a different approach to dealing with drug cartels from that of his predecessor, Oaxaca is back in business. But will the current surge in tourism continue, and be enough to enable the city’s bars and cantinas to turn a reasonable profit (let’s forget about the well-known downtown Oaxaca “not-for-profit” mezcalería), and warrant the opening of more mezcalerías? On all counts, I would suggest so. Mezcal will continue to positively impact the level of tourism in the state capital. There are several reasons to opine that more mezcalerías than the current (early 2016) 15 or so will open, and that the existing ones will not only survive, but continue to thrive. There are numerous reasons for this perspective. It is trite that the profit margin for retail spirit sales is significant; more so in Oaxaca than for example in the US or Canada, since tourists are accustomed to hometown elevated prices (which of course take into consideration cost of export, import tax, warehousing, agency fees, etc.) and are more than willing to pay what amounts to half the cost of a shot as compared to in their home towns. Bars can sell a 1.5 ounce serving of mezcal tobalá for 120 pesos ($7 USD) or more, without patrons batting an eyelash. Average cost to the retailer for this type of mezcal is in the neighborhood of 250 pesos per liter, perhaps a bit more. This is not to suggest that tourists are easy marks, but rather simply that profit margins for mezcal here in Oaxaca are as healthy, if not healthier than in the US, Canada, the UK, and elsewhere. On the contrary; Oaxacan mezcal prices remain a bargain. In theory, only mezcal which has been certified by a regulatory board, Consejo Regulador del Mezcal, can be sold in Oaxaca. There are costs associated with certification, and tax on a bottle of this kind of mezcal is extremely high. However, many mezcalerías in Oaxaca sell quality “mezcal” which is called destilado de agave, or is known by a similar name. Sale of this alternate agave based spirit (yes, still a mezcal) nets a significantly higher gross profit. Sometimes but not always, the lesser cost to the retailer is passed on to the customer. Another way that some mezcal cantinas have kept the cost down to consumers is by offering servings at one ounce servings (i.e. La Mezcalerita). Some Oaxaca mezcalerías serve food (i.e. el Destilado), which broadens the pool of prospective patrons to include spouses and others in a party who are not all that enamored with the spirit. While the profit is of course less with food as compared to with spirit, offering a quality comida or cena certainly helps to pay the bills. Other mezcal bars serve cocktails (i.e. El Espino Gastro Cantina), having a similar effect as those which go the cuisine route to keep their establishments filled. While some in the industry decry the bastardization of mezcal by using it to make cocktails, even such “purists” have begun to come around and have used a “cocktail night” as a way to attract customers. You don’t need much space for a mezcalería (i.e. Los Amantes). It appears legal to sit, stand, and drink outside the bar on the street. Of course the closer the locale to the heart of Oaxaca’s downtown historic core, the higher the rent and the more modest the square footage, and thus the need for lax, if any, imbibing laws. On the other hand, with a bit of good publicity, a welcoming vibe and quality hooch, one can have all the space needed and a presumably affordable rent if at the fringes of downtown (i.e. Cuish). Oaxaca is one of the poorest states in the country. Concomitant is the fact that wages are low, though retailers would be hard-pressed to encounter reliable staff at anywhere close to minimum wage, unless healthy gratuities are the norm. Thus, wages can be the most modest expense in a mezcalería’s cost equation. But it cuts both ways; low wages can mean staff of questionable quality, so it becomes incumbent upon mezcal bars to keep a close watch, with owners close at hand. However, quality personnel can be affordable in this industry, since many bars do not open until the afternoon. Thus, a single shift can keep wages in check. Often family members and partners maintain hours of operation (i.e. respectively Mis Mezcales and In Situ). In such cases reputations are built upon friendliness, helpfulness and the knowledge of those staffing the mezcalería (i.e. Mis Mezcales) often combined with quantity and diversity of product (i.e. In Situ boasts 180 different mezcals). With the cost of mezcal purchased wholesale in quantity still extremely modest (i.e. as low as 60 pesos per liter for espadín), establishments can afford to be well-stocked. Market saturation of mezcalerías in Oaxaca is a long way off. No doubt tourism in Oaxaca will continue to have its ups and downs. But spirits enthusiasts seem immune to the fear-mongering, and the urging by their friends and family against traveling to Mexico. The number of mezcal aficionados continues to grow, as does the diversity in their objectives: restaurant / bar owners visiting with their staff for training purposes; entrepreneurs with export aspirations; scotch, brandy and tequila drinkers anxious for something new; and of course novices wanting to sample and learn. Alvin Starkman is a permanent resident of Oaxaca. He operates Mezcal Educational Excursions of Oaxaca (http://www.mezcaleducaitonaltours.com). Alvin can be reached at [email protected]. |

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed